|

|

|

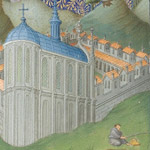

Above: Folio 1r, Folio 97v, and Folio 149r from the Belles Heures of Jean of France, duc de Berry, 1405–1408/9. Herman, Paul, and Jean Limbourg (Franco-Netherlandish, active in France by 1399–1416). French; Made in Paris. Ink, tempera, and gold leaf on vellum; 9 3/8 x 6 5/8 in. (23.8 x 16.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1).

Welcome to the journey through the illuminated pages of the Belles Heures manuscript, occasioned by the current exhibition The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. While the exhibition is on view, now through June 13, 2010, I will post weekly discussions of one or more sections of the manuscript. I welcome your comments or questions—about the weekly posts or about the exhibition itself. (See About This Blog for more information about submitting comments.) Above all, I hope you will enjoy the richness of images presented here from the pages of the glorious Belles Heures; see Manuscript Pages for a complete list of images of the illuminations from this magnificent manuscript.

As we look together at the sections and pages in detail, we’ll find sumptuous color and delicate line; elegant, swaying postures and violent, bloody action; landscapes rendered with a new sense of verisimilitude and patterned backgrounds rooted in medieval tradition. We will not only see gold on every page, but also human expression and the Christian iconography of divine salvation.

A special advantage of this online presentation is that we’re able to look at all the pages in the original order of the bound manuscript. In the exhibition galleries, the sections of the manuscript are presented in order, but—because of the nature of how books are made—the physical pages are not. In the galleries, the unbound pages of the manuscript are seen as bifolia. A bifolium is a folded sheet of parchment comprising four pages. Manuscripts are made by binding together a series of quires, or gatherings; each quire is composed of several sheets of parchment folded in the middle and sewn together. If you imagine four sheets of parchment folded and gathered in this way, you can see that the first page is actually on the same original sheet as the last page. Accordingly, in the exhibition, the leaf with the calendar page for January (Folio 2r) also includes the page for December (Folio 13r).

Manuscripts are either paginated (a number for every page) or foliated (a number for every folio). The Belles Heures is foliated. Each bifolium has two folios, and each folio has a recto and a verso. (Rectos are on the right, versos on the left.) In the reproductions here, every image from the manuscript is identified by its folio number and labeled either recto (”r”) or verso (”v”). (For more about book construction, watch the video The Structure of a Medieval Manuscript on www.getty.edu, or read the essay “The Art of the Book in the Middle Ages” in the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.)

My sequential introduction to the Belles Heures—and to books of hours in general—relies on the work of a few scholars whose publications I would like to acknowledge and recommend to anyone interested in further research. For the Belles Heures itself, the now fundamental and indispensable work is The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry by Timothy B. Husband, curator of the current exhibition. The seminal work on the art of the Limbourg brothers and the patronage of Jean de Berry is by Millard Meiss. For information about books of hours in general, the best source is Roger Wieck. All of these books have informed my writing here, and I am grateful to their authors. (See detailed citations below.)

The major sections I will discuss, in order, are: Calendar Pages; The Saint Catherine Cycle; Prayers to the Virign and The Hours of the Virgin; The Seven Penitential Psalms; The Great Litany and the Hours of the Cross; Diocrès, Bruno, and Carthusians and the Office of the Dead; The Hours of the Passion; The Suffrages of the Saints and Heraclius and the True Cross; The Story of Saint Jerome; The Saints Paul and Anthony Cycle; and Masses, Prayers, and the Story of Saint John.

A few of the texts and some of the pictures included here fall outside these major sections of the manuscript. One of these is the first page, the ex libris shown above (see full-size image), proclaiming that the manuscript belongs to Jean de Berry. While the text does not name the manuscript as the Belles Heures, we know that the title comes from the time of the duke. Like many members of his age and class, Jean de Berry and his staff kept meticulous records and inventories of his collections, including the description “Item, unes belles Heures, très bien et richement historiées…,” which goes on to indicate the order of the pages that matches the Belles Heures.

—Wendy A. Stein, Research Associate, Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Sources:

Husband, Timothy B. The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008.

Meiss, Millard. French Painting in the Time of Jean de Berry. 5 vols. New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1967, 1968, 1974.

Wieck, Roger S. Time Sanctified: The Book of Hours in Medieval Art and Life. New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1988.

———Painted Prayers: The Book of Hours in Medieval and Renaissance Art. New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1997.

Tags: bifolia, bifolium, introduction, parchment, quire

March 3, 2010 at 11:42 AM

Hi,

Congratulations for the exhibition. Unfortunately I live in Brazil and won’t be able to profit from this wonderful and unique opportunity as I’ll be in NY only on July! At least I can “follow” all the information posted here… I would like to understand the relation between this manuscript and the Plus Belles Heures du Duc de Berry (in France). Which one was done first? What are the differences? The Belle Heures is really in better shape than the French one?

Best Regards,

Marcia

March 3, 2010 at 2:16 PM

Dear Marcia,

Thank you so much for being the first to post a comment on this blog! Your question is excellent, but I am not sure what manuscript you have in mind. There are two possible candidates: the Très Belles Heures de Notre-Dame, (Paris, BN, Nouv. Acq. Lat. 3093) and the Très Riches Heures (Chantilly, Musée Condé, Ms.65). I think it is likely you mean one of these as there is no book associated with the Limbourg Brothers or Jean de Berry called the “Plus Belles Heures.”

The Très Belles Heures had a complicated history of production. It includes a great variety of styles by different artists working over a period of over three decades, and working for different patrons. As early as 1384 Jean de Berry commissioned the artist known as the Parement Master to decorate this book of hours, and work stopped and started on it several times. Sometime between 1404 and 1406 the Limbourgs contributed a few illuminations.

However, I think it is more likely that the book you had in mind is the Très Riches Heures, which is the most famous of the manuscripts including work by the brothers. In fact, some would call it the most famous manuscript in the world, perhaps rivaled only by the Book of Kells (which is a different story altogether). With this manuscript I can answer your questions:

Which was done first?

The Belles Heures was done first, begun around 1405 and finished either late in 1408 or early 1409. The Très Riches Heures was begun around 1411 or 1412 and was left unfinished when the artists and the patron died in 1416. Other artists completed some pages after the Limbourgs’ designs, and added other miniatures as well.

What are the differences?

The BH is the only manuscript completed in its entirety by the Limbourg brothers—by comparison, the TRH is a fragment. But what a fragment! The boys had matured as artists and their achievements in the TRH in the depiction of light, of landscape, and of the human form took a giant leap, moving the history of art in the north forward toward the future. Their most famous work was in the calendar pages such as January and February, the latter an extraordinary winter landscape.

Is the BH in better shape?

As I mentioned above, the BH is the ONLY book of hours completed by the Limbourg Brothers. The TRH includes many illuminations by later hands. The BH is in excellent condition, largely because for most of the six hundred years since its completion it was a bound book, kept closed and away from light, and owned by noble, wealthy, and careful private owners, who must have handled it with respect.

March 3, 2010 at 2:57 PM

Dear Wendy,

I really did meant the Très Riches Heures (at Chantilly). Sorry for the misunderstanding. Thank you so much for your answers. They were great! I’m taking the opportunity to read, appreciate and observe, page by page, the BH on line. I intend to use this channel to ask and learn more in the near future!

Best Regards,

Marcia

March 4, 2010 at 8:32 PM

Dear Wendy,

How great to learn about this incomparable opportunity to see multiple pages of the Limbourg brothers’ work all in one visit! I can’t wait to get to NY from Boston to see this.

My question is about the provenance. The information included in the Met database suggests a huge 400+ year gap of known ownership. Is the data for this period of ownership really unknown? And how did the book move from the Geneva Rothschilds to NY? Was it sold by the family through Rosenberg and Stiebel?

Thank you,

Paul Richardson

March 5, 2010 at 10:34 AM

Dear Paul,

Thank you for your enthusiasm and your intelligent question. There is indeed a big gap in our documented knowledge of the owners of the Belles Heures. We know it was bought from the estate of Jean de Berry by Yolande of Aragon, Duchess of Anjou, in 1417. We next know of it in 1879, when its noble owner was Pierre-Gabriel Bourlier, baron d’Ailly. The Rothschild family were the next owners, and it was sold to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1954 by Hans Stiebel of the firm Rosenberg and Stiebel, as you rightly surmised. These few facts will be illuminated and expanded in an illustrated public lecture to take place at the Metropolitan Museum on Sunday, April 11 of this year. On that day Christopher de Hamel of the University of Cambridge will be speaking on “The Belles Heures since the Duc de Berry” at 2:00 p.m. in the Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium. He is a splendid, smart, and entertaining speaker and an expert on the provenances of medieval manuscripts. I highly recommend this event. More information is available in our calendar.

March 5, 2010 at 5:03 PM

Congratulations, Wendy, on the consummation of all your efforts to help make this wonderful exhibition a reality. It will be a delight to look at the Belles Heures along with you, and I very much look forward to more of the blog. Although I know some of the images well, many of those I had the pleasure of seeing on Monday were entirely new to me.

Soon,

Deirdre

March 6, 2010 at 9:16 PM

Dear Wendy,

I second the other contributors–this is a fantastic site, and your responses are so informative. I have two questions. The first concerns the duration of this blog and whether the webpages will be available after the exhibit closes. I teach a course that includes medieval manuscript making and the history of the book, and I would love for my graduate students to have access to the pages and commentary in future semesters. My second question is whether Christopher de Hamel’s lecture will be available online (a transcript thereof or podcast)? My students quite enjoyed his “Medieval Craftsmen: Scribes and Illuminators,” but since we’re in Texas we will not be able to attend his April 11th talk.

Thank you, and best wishes,

Nicole Smith

March 8, 2010 at 9:10 AM

Dear Deirdre,

Thanks so much, Deirdre! See my full expression of gratitude at your marvelous blog, The Medieval Garden Enclosed.

With springtime warmth,

Wendy

March 8, 2010 at 11:57 AM

Dear Nicole,

Thank you so much for your kind words – I am so glad you enjoy the site (next post later this week). I will be writing weekly for the duration of the exhibition (which closes on June 13), but the site will still be accessible afterward for the ongoing enlightenment of your students and others. Good news also about Christopher de Hamel’s lecture: it will be recorded live, and within about three or four weeks after April 11, it will be posted on the Museum’s YouTube channel and iTunes U; there will be link to the video from this site.

Thanks again,

Wendy

March 8, 2010 at 9:46 PM

Dear Wendy: Like the other posters, I want to congratulate you for the wonderful exhibition that –thanks in large part to your blog –will continue to engage us long after our visit to the Met! But unlike the other posters, I knew virtually nothing about medieval manuscripts before viewing the Belles Heures, and have a basic question: Why are the images in these manuscripts called “illuminations”? Is it a reference to the illuminating effect of the gold and silver paint? Or to the illuminations of the spirit the paintings and the text promise to inspire in the reader? I admit I’ll be a bit disappointed to learn that “illumination” is simply a synonym for “illustration”, but whatever the answer, thank you for the illumination.

March 9, 2010 at 1:16 PM

Dear Mark,

Thank you for your engagement with this material. The mundane answer is, yes, they are called illuminations because of the use of silver and gold creating luminous effects. But the use of the terms illumination and illustration opens some profound and interesting issues around the relation of image and text. I generally refer to the paintings in the Belles Heures as illuminations—one could also call them miniatures, or pictures or paintings. But I reserve the word illustration for situations where the image genuinely illustrates the text, that is, tells the same story as the text. One of the things that fascinates me about books of hours is that the pictures often serve as a parallel meditative theme, not illustrations. Both illustration and illumination come from Latin words that relate to light, but they shed that light in different ways.

Thanks for a deceptively profound question,

Wendy

March 11, 2010 at 10:38 AM

Hello. I’m one of a Japanese and interest in this exhibition.

I lead the explication of this exhibition and I have a question. What is a “a select of precious objects from the early fiftheenth-century”. Can we watch some of objets d’arts of fifteenth-century or only the manuscript of Jean de Bery?

March 12, 2010 at 4:52 PM

Dear Amandine,

Thank you for your interest in this exhibition. The exhibition’s main focus is the manuscript called the Belles Heures, and this blog is intended to be about that manuscript. However, it is true that the exhibition galleries include a few precious objects reflecting the taste of the Valois courts, that is, the family of the Duke of Berry. Of the objects from the Met’s permanent collection, the following can be seen in the Collection Database: The Entombment of Christ (1982.60.398); The Dead Christ with the Virgin, Saint John, and Angels (17.190.913); Mourners from tomb of Jean de Berry (17.190.386 and 17.190.389); and Saint Catherine of Alexandria (17.190.905).

Thanks again for your interest in the exhibition.

—Wendy

March 17, 2010 at 4:42 PM

Dear Wendy,

I recently traveled from Virginia to New York specifically to see the Belles Heures and the Hours of Catherine of Cleves exhibitions. It was very gracious of you to recommend the Morgan Library’s exhibition. These two exhibitions, along with the Mourners at the Met, were simply stunning and an once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. In my opinion, these two illuminated manuscripts represent the pinnacle of art. I collect art books for a hobby and highly recommend the beautiful and informative catalogues of all three exhibitions. To me, these catalogues are the ultimate art books. Thank you and everyone else involved in these incredible exhibitions.

Best regards,

Randall T. Clark

March 26, 2010 at 3:04 PM

Dear Wendy,

I’m returning to the blog, profiting from this unique opportunity to better understand the Belles Heures through your comprehensive answers!

Today I would like to ask several questions related to the manufacturing of the book:

Which material are the pages made of?

What kind of materials was used to paint? Regular pigments like in frescoes, tempera, etc.? And to preparation (water, glue, yolk, oil,…)?

How did they manage to paint both sides of the page? I mean, how did they paint one side without damaging the reverse?

Best Regards,

Marcia

March 26, 2010 at 4:37 PM

Dear Marcia,

Thanks for your new questions – I know they are of interest to many observers. I want to get back to you quickly, but may come back to these questions in greater depth later.

The material the book is made of is parchment or vellum, made from the skin of a calf, sheep or goat – most likely calf in this case. You can look at the Pen and Parchment blog for more info.

The pigments are mineral and organic pigments, coming from natural substances. The most expensive pigment is the blue called ultramarine, which comes from the semiprecious stone lapis lazuli, and that stone came from Afghanistan.

The artists mixed these pigments with a binding medium, most likely glair, which was egg white, but also likely gum arabic.

Painting both sides… gotta think about that one!

Hope this helps for a start.

Best,

Wendy

March 27, 2010 at 11:59 AM

Thank you for a beautiful site.

More on materials: You mention as binders “glair” or “gum arabic.” Has there been any chemical analysis done to confirm? Too destructive? Was there any yolk used as binder?

March 29, 2010 at 12:26 PM

Dear Karen Kvavik,

Thank you for your comment and question. Margaret Lawson, the lead conservator of the Belles Heures, wrote an excellent article on technical matters concerning the manuscript, which appears in the appendix to The Art of Illumination, the monograph by Timothy Husband previously cited. She wrote, “It is not possible to identify the binding media used in the Belles Heures pigments by non-destructive analysis at this time.” However, she went on to give suggestions based upon “historical treatises, visual observations, and personal experience using medieval materials.” She notes that glair (made from beaten egg white) had been the most frequently used binder, but by the fifteenth century was being used with or replaced by gum arabic made from acacia or plum. She cites, among other sources, The Craftsman’s Handbook, by Cennino Cennini (1437). She also notes that other binders used in the medieval period included egg yolk, casein, fish glue, and parchment size.

March 29, 2010 at 4:32 PM

Dear Wendy,

No analysis of the binding media were undertaken in the Belles Heures, since this would have involved the removal of a microscopic sample. Glair, gums, and also egg yolk are the possible binders used, based on what the treatises recommend. Even different binders were most likely used for different paint colors in the same manuscript, but all this would have to be confirmed by scientific analyses.

[Editor's Note: Silvia Centeno is a chemist in the Museum's Department of Scientific Research.]

March 30, 2010 at 9:16 PM

I just wanted to post because I’ve been fortunate enough to visit the exhibition and I really appreciated the magnifying glasses provided by the museum. Wonderful; I just wish it were possible to have those at every single exhibition of drawings, and even at the drawings gallery on the second floor.

Great also to have the blog; the images online are so bright an beautiful. I just love the Met.

April 1, 2010 at 12:19 PM

Dear Wendy,

My husband and I traveled up to New York from Virginia this past weekend to see both the Met’s illumination exhibition and the one at the Morgan Library. Both were absolutely breathtaking and we learned a lot! But one big question I have has not been answered: how did the artists paint such small pictures that are so detailed, especially expressions on faces? Did they use magnifying glasses as they painted? And what about brushes — were they made of one horsehair or something like that? I’m just amazed by it all. Do one of the sources listed above deal with this subject? Thanks.

Sharon

April 1, 2010 at 8:50 PM

Dear Rina,

Thank you so much for your appreciative words and your enthusiasm. I too love having the magnifying glasses. They add so much to my appreciation of the wonder of these miniatures as well.

Dear Sharon,

How wonderful that you and your husband traveled up from Virginia to visit these manuscripts! I am glad you found them breathtaking – and worth the trip!

As to questions of magnification, brushes, and other technical matters, these are of interest to many readers. Among the books already cited, the one by Timothy Husband has an excellent appendix by Margaret Lawson, who was the principal conservator of the Belles Heures, and I recommend it for all sorts of interesting information about the manuscript. For general information about techniques, I love a little paperback by Christopher de Hamel, part of the Medieval Craftsmen series, titled Scribes and Illuminators. According to this book, brushes were made from tail hairs of miniver or calaber (species of ermine and squirrel), tied and inserted into a feather. As to the question of the artists using magnification, we assume they did. According to De Hamel, pictures of painters wearing eyeglasses can be found as early as the fourteenth century.

Wendy

April 14, 2010 at 3:00 PM

Like Carravigio, Michaelangelo and Raphael who pictured themselves in their art, would the brothers have pictured themselves in any of the illustrations?

What a spectacular exibition both the Met and the Morgan has put on for a once in a lifetime viewing. This should not be missed by anyone who loves illuminated manuscript.

Roy I Jones

Charlestown, RI

April 14, 2010 at 5:45 PM

Dear Roy Jones,

Many thanks for your enthusiasm about the exhibition and for your question. Raphael, Michelangelo, and Caravaggio all worked at a later time than the Limbourg brothers, when the identity of the individual artist was more widely recognized. I do not expect there are any self-portraits of the Limbourgs in the Belles Heures, but we will never know.

Wendy

May 4, 2010 at 6:06 PM

This is a great exhibit and I am sorry it is going away so soon. I have a question about the two illuminations of the solders outside the tomb of Christ. The exhibit label describes the interesting detail of what looks like a sun in one and possibly a moon in the other, as masks. I assumed that they were the artists interpretation of Roman shields. Why does the Met identify them as masks? Thanks for your time!

May 5, 2010 at 1:06 PM

Dear Ruth,

Glad you liked the exhibition. You are right, the faces are on shields. I am sorry a colleague’s description of the faces as “masks” was confusing for you. I refer to them as faces in my post on the Hours of the Passion.

Wendy

June 1, 2010 at 9:08 PM

My wife Mary-Jo and I enjoyed the exhibition enormously this past weekend. Being able to see all the pages of the manuscript was a rare and wonderful opportunity. Which made us wonder: Why is it necessary to re-bind the manuscript? Why not leave the pages unbound and keep them on display as they are now?

June 2, 2010 at 1:55 PM

Dear Karl,

Excellent question! Important question. I am sure you noticed the excellent condition of the paintings in the manuscript when you visited. Perhaps you marvelled at the brilliance of the color, the gleam of the gold, the minute brushstrokes. Part of why they are in such good condition is precisely because they were bound in a book, kept closed and clasped, protected from dust, air, and light for most of the time. Kept clasped, parchment stays flat, but release it and over time it will try to go back to the shape of the sheep, cockling and causing the pigment to flake. Exposed to light, colors fade. Exposed to air, other pigments may oxidize. Having a book bound is in itself a conservation technique. Furthermore, the Met got this splendid object in the form of a book. It was made to be a book. It must become a book again. It would be a crime against sound museum practice for the Met to keep it permanently dismembered. The responsibility of the Museum is to do its best to preserve and protect the objects in its care, and rebinding the Belles Heures, using the original sewing holes left from the first binding, will be part of that charge.

Wendy

July 27, 2010 at 5:40 PM

Dear Wendy,

How I wish I had known about your exhibit – I would have flown to NYC just to see these illuminations in person. As an artist and illustrator, I’ve always been drawn to small detailed works, and the historical context of these are worthy of more study on my part. I will revisit again, as I bookmark this page for my “inspirational” web surfing. I’ll be transported in time and feeling regret in having to drag myself back to my painting!