|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

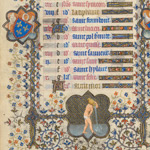

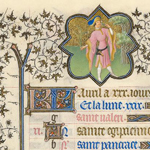

Nearly all books of hours began with a section of calendar pages, to help the owner keep track of saints’ days and holidays throughout the year. Local variants in the veneration of saints, combined with the personal tastes of individual patrons, make calendar pages a rich resource for scholars seeking to localize a manuscript. In the Belles Heures, the calendar page for each month begins on the recto (right-hand page) and ends on the verso (left-hand page). For every month, the first line begins with a decorated “KL” for Kalends, the traditional Roman name for the first day of the month, followed by gold text that gives the name of the month and the number of solar days in French with Roman numerals (e.g., Janvier a xxxi jour). The next line gives the number of lunar days. The text on the rest of the page is divided into four columns: the first two follow complex calculations that were used to determine the date of Easter. The third column comprises abbreviations for the Roman naming of dates: Kalends, Nones, and Ides. The fourth, wider column names the saints and holidays, alternating red and blue ink but with major feasts in gold. (In many lesser books of hours, most of the feasts are listed in black, and major feasts in red???hence the phrase “red-letter day.”) In the Belles Heures, each month begins with a quatrefoil medallion at the top containing a picture of the traditional labors or activities of the month, with another medallion at the bottom containing the zodiacal symbol.

The borders for January and December are more elaborate than those for the intervening months, with twining decorative elements along the sides and, more significant, additional quatrefoils displaying the duke’s coat of arms. In January, the shields are held by swans, one of the duke’s emblems. In December, the swans are joined by bears, his other emblem.

|

|

|

Tiny as they are, the representations of the months demonstrate the attention to detail and specific class representations for which the Limbourg brothers became famous. The image of February’s man warming his hands includes a believable interior with a fireplace and smoke curling up the chimney, as well as the substantial figure seated by the hearth. The scanty clothes worn by the men in July’s harvest scene intimate the heat of the day, and the background includes a full landscape in compressed form. A whole forest is suggested in November’s feeding of the pigs. In these little pictures, the future of Northern Renaissance landscape painting is prefigured.

While the labors of the months and signs of the zodiac are represented with innovative details by the artists, the tradition of representation to which they belong derives from the Classical past. Gothic structures such as the cathedrals of Chartres and of Paris include representations of months in their sculptural programs. In fact, the comparison with cathedrals is apt: just as the sculptural and stained-glass programs of those monumental structures of the twelfth through the fourteenth centuries presented an encyclopedic view of the world and Christian theology, a book of hours as fully decorated as the Belles Heures encompassed a cathedral in pocket form, with Christ???s childhood and passion, and all of the stories, saints, and devotional images included.

The calendar pages of the Belles Heures have been explicated in another Metropolitan Museum blog, The Medieval Garden Enclosed. This marvelous resource written by The Cloisters’ Deirdre Larkin has enabled me to see the labors of the months with new eyes and to understand the medieval cycle of the year in the contexts of horticulture, philosophy, art, history, literature, religion, magic???it’s all there; you must check it out.

???Wendy Stein

Tags: Easter, feasts, holidays, ides, kalends, lunar, medieval calendar, months, nones, solar, zodiac

April 7, 2010 at 11:14 AM

[...] February, July, and September calendar images from the book of Belles Heures / All images from The Metropolitan Museum of Art [...]

April 7, 2010 at 11:22 AM

Thank you so much for breaking down the structure of the calendar pages. I’m mesmerized by the border decoration on all the pages, but especially by the vignettes on the calendars. I can’t wait to come back to the exhibit to see these in person again. I’m so glad to know the blog will remain up as a resource, as well. Thank you so much for sharing your compelling writing and insights!

April 7, 2010 at 3:34 PM

Dear Maggie – Thank you so much for commenting on the Calendar Pages. I, too, find them more and more engaging, and keep going back to look at them again. I love the ways in which we can find in them the roots of so much later development, both of the Limbourg brothers themselves, and of the history of art generally. The detail of tools and activities in the agricultural scenes especially are such a window into the artists’ interests. And the postures of the noble folk — such attitude!

Wendy

July 26, 2010 at 11:26 PM

I love the colors in these images. They remind me of some beautiful tile work I saw when I visited Florence once many years ago. Its interesting to imagine the stories and lives depicted in the pictures – how different from our lives today!!

July 26, 2010 at 11:30 PM

I’d like to get a sense of the scale here. What are the dimensions of the actual pages? Are the calendar pages full size in the book or just partial? Thanks!

July 28, 2010 at 11:33 AM

Dear Nancy,

Thank you for your interest and question. If you click on any thumbnail image in this blog, you will get a picture of the full page in the manuscript, including a detailed caption that includes the size, very roughly 6 1/2 by 9 inches. That includes the border and outer margin. Calendar pages conform to this size – but do look at the full page image, not just the thumbnail, to get a sense of the scale of the illumination on the full page: the images of the labors of the months and zodiac are very small, closer to one inch square!

Wendy