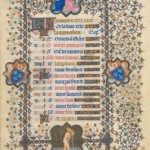

Above left to right: Calendar page from The Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry, 1405???1408/1409. Pol, Jean, and Herman de Limbourg (Franco-Netherlandish, active in France, by 1399???1416). French; Made in Paris. The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1). Center: Detail of the activity for the month; Right: Detail of the zodiacal symbol Aquarius. See the Collection Database to learn more about this work of art.

Januar By thys fyre I warme my handys; Februar And with my spade I delfe my landys. Marche Here I sette my thynge to sprynge, Aprile And here I here [hear] the fowlis synge. Maij I am as lyght as byrde on bowe, Junij And I wede my corne well I-now [enough] Julij With my sythe [scythe] my meade [meadow] my mead I [mow]; Auguste And here I shere my corne full low. September With my flayll I erne my brede, October And here I sawe [sow] my whete so rede. November At Martynesmasse I kyll my swine; December And at Cristesmasse I drynke redde wyne. (Bridget Henisch, The Medieval Calendar Year, 1999)

The calendar pages of Books of Hours are embellished with depictions of seasonal occupations that are both a delight in themselves and a rich source of information about the cycle of the medieval year. The activities depicted in these calendar scenes ultimately derived from classical tradition, and were highly conventionalized, but variations on the themes do occur. The activities for the winter months are often set indoors, whether feasting, warming by the fire, or the like. The spring, summer, and autumn scenes are either agricultural labors like pruning, reaping, or sowing grain, or scenes of hawking, hunting, or other outdoor pleasures. The calendar scenes have their literary counterparts in medieval almanacs and calendrical poems like the one above, from a late fifteenth-century manuscript in the Bodleian Library.

In the image from the Belles Heures shown above, the month of January is represented by two men, one young and one old, seated back to back. The young man on the left drinks from a full bowl, while the old man on the right reaches for a large jug to fill his empty one, although the water, like the old year, has run out (Timothy B. Husband, The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry, 2008). The image evokes the double-headed divinity Janus, the god of thresholds and of beginnings and endings who gave his name to the first month of the year in the Roman calendar.

One of the more typical activities for the first month in medieval calendar scenes is feasting, as in the January page of the Tres Riches Heures, also made for the Duke of Berry. Despite the Church???s disapproval, customs associated with the Roman New Year festivities continued unabated throughout the Middle Ages, and both banquets and gifts were given at that time.

According to the medieval theory of the humors, a healthy balance in the body could be achieved through dietary prescriptions. In winter, the dominant humor was phlegm; hot and fatty foods were to be eaten, and warming wine to be drunk, in order to combat the cold humor. Because the heat of the body was believed to be drawn inward in winter, it was thought that such foods were easier to digest at that time of year (Marie Collins and Virginia Davis, A Medieval Book of Seasons, 1992).

Although January began with the New Year???s feast, the working year resumed once the feast of the Epiphany was past. While the winter months were a break from work in the fields, woodcutting, animal husbandry, and many other activities continued, although they were not commonly represented in the conventional calendar scenes:

January

When Christmas is ended, bid feasting adieu,

go play the good husband, thy stock to renew.

be mindful of rearing, in hope of a gain,

dame profit shall give thee reward for thy pain.Thos. Tusser, Five Hundred Points of Husbandry, 1557 (Dorothy Hartley, Lost Country Life, 1979)

—Deirdre Larkin

Tags: Belles Heures, calendar, feasting, January

January 24, 2009 at 10:24 pm

I discovered this blog about a month ago and I love it. I majored in art, and I loved learning about the Medieval Period. The Belles Heures is a beautiful book. I enjoyed reading Pope’s amusing thoughts on topiary, too. I’m one of those who never read them. Your explanations are so interesting and detailed. I live in NYC, so I have been to a few of your garden talks. They are so wonderful and informative. Also, the Cloisters is a great place to be, especially the gardens. Any avid gardener who loves herbs and/or the Medieval Period would love this blog. It’s obvious that you enjoy sharing your knowledge. Thanks, Cathy

January 26, 2009 at 1:36 pm

Hi, Cathy—

The Belles Heures is indeed very beautiful. I look forward to using the calendar pages for the first post of each month, and to the exhibition downtown next September. I’m glad you enjoyed the Pope—I hesitated to include it, because it’s so late in date, but it’s so funny that I couldn’t resist. Please do introduce yourself if you come to The Cloisters for a talk or just for a visit—I would be happy to spend some time in the gardens with you.

February 3, 2009 at 9:58 pm

I loved this post. I am fascinated with medieval artwork, and this calendar portion of the book of hours really tells us so much about life back then. thanks for all the information and the poem.

July 11, 2009 at 6:24 pm

I am interesting in this Book of Hours. I have about 40 images from it. But why this image is so small?

July 24, 2009 at 8:31 am

Dama May—if you click on each image in the post, you will find another page with an enlarged image and additional text. All the calendar posts based on the Belles Heures follow the same format, and you can find more information about the feasts and activities proper to a given month, as well as the zodiacal sign assigned to it, on those pages.