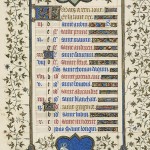

Above, from left to right: Calendar page for March, from The Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry, 1405???1408/1409. Pol, Jean, and Herman de Limbourg (Franco-Netherlandish, active in France, by 1399???1416). French; Made in Paris. The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1); detail of the activity for the month; detail of the zodiacal symbol Aries. See the Collection Database to learn more about this work of art.

The name “March” is derived from Martius, the Roman god of war, fertility, and vegetation. In ancient Rome, military campaigns traditionally began in the spring, which also coincided with the return to agricultural labor in the fields after the winter rest.

In the medieval calendar tradition, the most characteristic activity for the month of March was the pruning or cultivation of the still-dormant vine stocks that would produce wine grapes. By medieval times, wine grapes were widely cultivated throughout Europe; their culture had been introduced from the Mediterranean into Germany and England by the Romans (see Roman viticulture), and they were grown as far north as climate permitted. The survey of properties in the Domesday Book???completed in the eleventh century for the King of England???includes thirty-eight vineyards.

Books of Hours produced in areas where wine grapes were not grown might instead show the plowing of fields in March. In either case???for vineyard or field???the breaking up of the soil was the first task of the new season. In the scene from the Belles Heures shown above, a man cultivates the soil around the vines with a mattock, while another man fertilizes the vines with manure; in the Tres Riches Heures, also produced by the Limbourg brothers for the Duke of Berry, one peasant is shown breaking up the soil in a vineyard, while two others have laid down their mattocks and are pruning the vines; the dung applied around each vine stands out clearly from the ground. In the foreground, a man furrows a field with a wheeled plow pulled by oxen.

Fields in medieval Europe were plowed in preparation for the sowing of spring cereals such as barley and oats, as well as legumes like peas. Thomas Tusser mentioned both crops in his Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry, 1557:

???Deirdre Larkin

Tags: grape, March, Vitis vinifera, wine

May 4, 2009 at 4:58 pm

Hello, Thea???

Henna (Lawsonia inermis) was an exotic plant imported from the East, and I very much doubt that the dried leaves would have been used to dye either cloth or skin in medieval England and Scotland. Madder (Rubia tinctorum) would have been a much likelier source of red. Henna is listed as a medicinal in the fifteenth-century Hortus Sanitatis; as Frank Anderson notes, confusion had been introduced into the herbal literature by Galen, who rendered the Arabic alhenna as alcanna. Henna was subsequently confused with alkanet , a red dye from the roots of Alkanna tinctoria that was used as a cosmetic in antiquity. (German Herbals through 1500, 1984).

The Highland Scots had their own dyes, and often used lichens. They also made use of the roots of bedstraw (Galium verum), a close relative of madder, to produce a fine red. (The flowers of bedstraw yield a yellow). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Traditional_dyes_of_the_Scottish_Highlands

May 4, 2009 at 4:59 pm

thanks, Deirdre. this was the info i was looking for. you???re the best!!