|

|

|

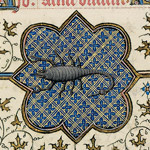

Above, from left to right: Calendar page for October from the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry, 1405???1408/1409. Pol, Jean, and Herman de Limbourg (Franco-Netherlandish, active in France, by 1399???1416). French; Made in Paris. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1); detail of the activity for the month; detail of the zodiacal symbol Scorpio. See the Collection Database to learn more about this work of art.

The annual cycle of cereal production that dominates the depiction of the agricultural year in the medieval calendar tradition began and ended with the sowing of seed corn. Scenes of tilling and sowing typically appear as the activity proper to October, before the arrival of the winter rains. While a plow was used to turn the earth in spring, a harrow was used to prepare the ground in autumn, as in the Tr??s Riches Heures. The harrow was also used to cover the seed once it had been sown. In the Belles Heures, as in many other calendars, a single sower represents the month, although a harrow appears at the edge of the scene.

In The Medieval Calendar Year, Bridget Henisch notes that the sower shown in calendar scenes is always male, although a woman may be shown walking behind him with a sack. Neither do women plow, but a female might be shown guiding the horse who draws the harrow.

In her masterly description of the art of sowing seed broadcast, Dorothy Hartley emphasizes that it was highly skilled and responsible work. (Depending on the grain and the weather, sowing was done either immediately after plowing or harrowing. ) The field to be sown was measured, and the seed was measured into open sacks that were set out at each end of an open furrow. The sower then walked smoothly and steadily down the furrow, counting his steps and keeping them even for the length of the field, guiding his feet down two adjacent plow lines. He then reckoned how many steps he must take to each handful of grain he would cast. (Field workers would not have been able to write or to count above ten, so agricultural tallies were kept by reckoning in four sets of five fingers, making a score.)

If a man sowed from a basket hanging from his neck, he might sow with his right and left hand in alternation. If he used a sowing cloth or apron, he would cast with one hand only and only to one side as he went up or down the furrow. Once the rhythm that determined how many handfuls of seed would be matched to the number of steps needed to cover the ground was established, it remained constant for the whole field. However, a skilled worker might be asked to sow more thinly or thickly in different parts of the field, which might be drier or damper in one place than another. He did this not by changing the rhythm, but by taking a little larger or smaller handful of grain.

???Deirdre Larkin

Sources:

Hartley, Dorothy. Lost Country Life. New York: Pantheon Books, 1979.

Henisch, Bridget Ann. The Medieval Calendar Year. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999.

P??rez-Higuera, Teresa. Medieval Calendars. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1997.

Husband, Timothy B. The Art of Illumination. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008.

October 8, 2009 at 2:41 pm

Write, OK, but whence the idea of counting being limited to fingers? The various sheep-counting rhymes that persisted in rural England till not long ago run up to twenty or even thirty, and those shepherds had no extra resources that the medieval sower didn’t.

October 13, 2009 at 11:06 am

Jonathan—Dorothy Hartley doesn’t maintain that agricultural counts were limited to ten, but that they were usually kept by thinking in four sets of five fingers, making up a score of twenty. She adds that most old agricultural counts do run in fours. There seems to be a fairly extensive literature on counting rhymes and songs—are there any sources that you recommend?