Coming to Fruition

Left: Blossom on espaliered pear tree. Photograph by Corey Eilhardt; Right: Fruit on the espaliered pear in Bonnefont garden. Photograph by Barbara Bell

Join us on Saturday, June 1, for a special Garden Day, celebrating the seventy-fifth anniversary of The Cloisters museum and gardens. We’ll be discussing our fruit trees in a daylong program of events, including talks on the significance of orchards and orchard fruit in medieval life and art, medieval fruits you can grow today, training and pruning espaliered trees like our famous pears, and the care of our beloved quince and other orchard fruits.

For related information, see previously published posts about our pear, medlar, and cornelian cherry trees.

—Deirdre Larkin

Angelic by Name, Angelic by Nature

Left: Angelica silhouetted against the blind arcade in Bonnefont cloister. Modern gardeners admire the bold, architectural qualities of angelica as an ornamental plant, but it has a long history as a useful herb. Right: The flower structure is typical of the carrot family to which it belongs. Photographs by Carly Still

Unknown to the Greeks and Romans, the beautifully named Angelica archangelica is a native of northern Europe. It can be difficult to determine whether it is this “garden angelica” or its close relative, A. sylvestris, that is under discussion in early sources, although Renaissance plantsmen like John Gerard distinguished between the two (see images of A. sylvestris in the wild).

When This You See, Remember Me

The forget-me-not’s associations with love and remembrance date to the Middle Ages, and were expressed in both the Old French and Middle High German names for this pretty little flower. Left: a pot of forget-me-nots on the parapet in Bonnefont garden. Photograph by Carly Still; Right: a young woman making a chaplet of forget-me-nots on the reverse of a portrait of a young man painted by Han Suess von Kulmbach. The legend on the banderole says “I bind with forget-me-nots.” See Collections for more information about this work of art.

A medieval symbol of love and remembrance that still decorated many a Victorian valentine, the forget-me-not (Myosotis scorpioides) was already known as ne m’oubliez mye in Old French and as vergiz min niht in Middle High German. The etymological and iconographic evidence for the forget-me-not’s medieval significance is ample, but the frequently repeated story of a German knight who tossed the forget-me-nots he had picked for his lady to her as he drowned, imploring her to remember him, is of the “as legend has it” variety. Margaret Freeman, who cites the use of forget-me-not as a token of steadfastness by several fifteenth-century German love poets, speculates that the color blue, associated with fidelity in the Middle Ages, may have contributed to the flower’s meaning.

Prymerole, Prymerose

This pretty yellow flower, gathered since the Middle Ages when “bringing in the May,” was known in Middle English by various names, including primerose, primerole, and cowslyppe. Photograph by Carly Still

Primula veris, literally the “first little one of spring,” was known in Middle English as prymerole and as prymerose, or “the first rose.” It was also known as cowslip, a name thought to be derived from “cow slop” or dung, perhaps because it grew in meadows and pastures where cattle grazed. The names prymerole and prymerose came from the Latin through Old French, and were shared with the cowslip’s relative, the common primrose (Primula vulgaris). As Geoffrey Grigson notes in his fascinating compendium of plant lore, The Englishman’s Flora, it can be very difficult to distinguish which of the two species is meant in early sources. Renaissance plantsmen like William Turner, John Gerard, and John Parkinson tried to clarify the confusion caused by the shared common names; as late as the eighteenth century, the great Swedish naturalist and taxonomist Carolus Linnaeus considered the cowslip, the common primrose, and the oxlip (Primula elatior; see image) to be forms of the same species.

Lungwort

Cowslips of Jerusalem, or the true and right Lungwoorte, hath rough, hairie, & large leaves, of a browne greene colour, confusedly spotted with divers spots or droppes of white: amongst which spring up certain stalks, a span long, bearing at the top many fine flowers, growing together like the flowers of cowslips, saving that they be at the first red or purple, and sometimes blewe, and oftentimes of all these colours at once.

???John Gerard, The Herball, or General Historie of Plants, 1597

The common lungwort or pulmonaria, growing under one of the veteran quince trees in Bonnefont garden. Native to central Europe, but widely naturalized, the early blooming lungwort is a denizen of damp, deciduous woodlands and hedgerows. The characteristic silvery-white spots scattered on its leaves were a sign of its medicinal value in treating lung complaints. Lungwort was already a common garden plant by the sixteenth century and many ornamental cultivated forms are now grown. Photograph by Carly Still

First Foot

Coltsfoot blooming in a pot in Bonnefont garden. The scaly stems and bright yellow blossoms of this early-spring-blooming member of the daisy family emerge well before the foliage; the hoof-shaped leaves appear only after the flowers have set seed. This notoriously invasive Eurasian species is best grown in a container. Photograph by Carly Still

Tussilago farfara, known in the Middle Ages under the Latin names ungula caballina (”horse hoof”) and pes pulli (”foal’s foot”), is still called coltsfoot, ass’s foot, or bull’s foot in English, pas-de-poulain in French, pie d’asino in Italian, and hufflatich in German. These names all derive from the fancied resemblance of the young leaf to the foot of a quadruped. See an image of the plant in leaf. A slideshow of images of Tussilago farfara in all stages of growth is available at Arkive.org.

Madder Red

No mader, welde, or wood no litestre

Ne knew; the flees was of his former hewe;

Ne flesh ne wiste offence of egge or spere.

No coyn ne knew man which was fals or trewe,

No ship yet karf the wawes grene and blewe,

No marchaunt yit ne fette outlandish ware.???Geoffrey Chaucer, The Former Age, ll. 17???22

Above, left: Dyer’s madder, a rough perennial herb native from the Eastern Mediterranean to Central Asia, grows in the bed devoted to plants used in medieval arts and crafts in Bonnefont cloister. The dried and pulverized roots of madder afforded a strong, fast red. Right: Detail from The Unicorn Defends Itself (from the Unicorn Tapestries). A range of colors???from pinks through bright reds, purplish reds, and oranges???could be achieved with madder, depending on the mordant used and the way in which the madder was combined with other colorants. (See Collections for more information about this work of art.)

The antiquity of the dyer’s craft is conveyed by Chaucer’s inclusion of the ignorance of madder, weld, and woad, the holy trinity of medieval dye plants, in his description of a period so remote and so devoid of the arts of civilization as to predate the use of knives, spears, coins, and ships. The use of madder is especially ancient, as demonstrated by this fragment of an Egyptian leather quiver in the Museum’s collection that may date to the 3rd millennium B.C.

Vegetable Gold

Incomparably the most important yellow in medieval painting is the metal gold. Yellow pigments, however, played a significant part in the pageant of medieval technique. One of the most important services required of them was to imitate the appearance of gold. Another of their chief functions was to modify the qualities of greens, and to a less extent, of reds. Of all their uses, perhaps the least important was to represent yellow things.

???Daniel Thompson, The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting

The vegetable yellows used in medieval illumination were more readily prepared and much safer to use than mineral yellows like realgar or orpiment. Above, left: The brilliant red-orange stigmas of the autumn-blooming saffron crocus, used by medieval cooks as a colorant and a seasoning, were also exploited by illuminators. Right: Flower spikes of weld, the most ancient yellow dyestuff known. When processed as a pigment, this weedy biennial provided manuscript painters with a bright vegetable yellow.

A number of plants were exploited for coloring matter in the Middle Ages, whether to tint foodstuffs or to furnish dyes and pigments. By no means all, or even many, artist’s pigments were of vegetable origin; mineral colors were used for wall painting, where the more delicate and fugitive nature of vegetable colors was inappropriate. In book painting, a combination of vegetable and mineral colors was employed. The same plant that yielded a dye for textiles could be prepared as a pigment and used by illuminators. Several species produced a viable yellow, including weld, saffron, and celandine; as Daniel Thompson observes, these vegetable yellows served both to imitate the appearance of gold, and to modify greens and reds.

Natural Symbols

The magpie in the leafless tree that spreads above the patriarchs and the bramble growing at the shackled feet of Man appear in a single scene from the magnificent allegorical tapestry Christ is Born as Man’s Redeemer (Episode from The Story of the Redemption of Man) on display at The Cloisters. Both the bird and the bush may be interpreted as symbolic expressions of Man’s fallen condition, which can yet be redeemed???the overarching theme of the series of ten hangings to which this work belongs.

Although the testimony of medieval bestiaries, sermons, allegories, and other sources encourage us to assign symbolic values to birds, plants, and animals, they are not always meant to bear a special meaning, and a very considerable range of meanings might be assigned to the same beast or plant. Sometimes exaggerated size or prominent placement is a clue that we are meant to pay special attention, but the possible significance of a natural symbol depends very much on the context of the individual work of art. I’d like to look at the magpie and the bramble shown above in the thematic context of human frailty, reconciliation, and redemption found in this tapestry.

The black-billed magpie (Pica pica) is a Eurasian species common in Europe and Britain. Before the seventeenth century, the bird was known simply as a “pie” or “pye,” from pie, the Old French rendering of the Latin pica, the feminine form of the name for woodpecker (see etymology), although magpies are corvids and are more closely related to crows, jackdaws, and jays than to woodpeckers. The English adjective “pied” or “piebald,” applied to particolored animals, is derived from the striking black-and-white plumage of the magpie. (The name for a baked dish with a pastry crust may ultimately have the same avian origin; see a related post on the blog The Salt).

Ancient and medieval natural historians were struck by the similarity of the magpie’s chatter to human speech (see, for example, The Natural History of Pliny), and the bird enjoyed a reputation for intelligence???an estimation borne out by modern research???but the character of the medieval magpie was as mixed as its plumage. The bird’s cleverness and its thieving habits were not altogether admirable; by the fifteenth century, a sly or wily person was called a “pye.” William Harrison, in the 1587 edition of his Description of England, tells a story of a chaplain, himself “the wiliest pye of all,” who persuades his patroness that the noisy magpies that pester her are not birds but souls in purgatory, clamoring for release. In a separate discussion of the birds of England, Harrison classes the magpie as an “unclean” bird, along with ravens and crows. According to the Continuum Encyclopedia of Animals in Art the magpie is associated with death in Western art, and appears as a “gallows bird” in the work of Northern painters like Pieter Bruegel the Elder (e.g., The Magpie on the Gallows) and Hieronymus Bosch. The magpie in Bosch’s Prodigal Son has been interpreted as an emblem of the prodigal’s soul, representing the phases of his conversion. The dual nature of the magpie, manifest in its black-and-white coloration, was also associated with frailty and inconstancy.

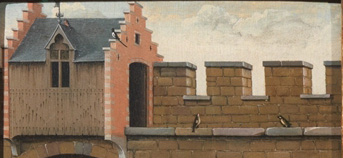

Magpies are frequently depicted in medieval art. In this detail from the left-hand panel of the Annunciation Triptych (Merode Altarpiece), a magpie perches high on the stepped gable above the entry to the courtyard of the Virgin’s house. (For a gallery of magpie images from medieval manuscripts, visit the Medieval Bestiary.)

I take the thorny bush at the feet of Man, which might look like a small-flowered wild rose at first blush, to be another member of the rose family, the common bramble or blackberry, Rubus fruticosus, with immature fruit. The unripe red “berry” of the bramble, actually a cluster of little drupelets, turns black as the fruit matures. (The ARKIVE website features a gallery of images of the common bramble in all its stages of growth, and a time-lapse video of the formidable speed with which it grows.) According to Genesis 3:17???18, thorns and thistles first came into the world when the ground was cursed after the fall of Adam and Eve. Thorny plants are often associated with error, sin, and the fallen state of humankind in medieval art. The black-fruited bramble was also associated with death. For another example of a thorny plant in an allegorical context of human frailty, also in The Cloisters collection, see Old Age Drives the Stag out of a Lake and the Hounds Heat, Grief, Cold, Anxiety, Age, and Heaviness Pursue Him, in which the stag representing Mankind leaps toward a large rosebush armed with formidable thorns.

For more information on the identification of plants in medieval tapestry, see

“Name That Plant” (January 28, 2011) and “Name That Plant, Continued” (February 5, 2011).

For further investigations into natural symbols in medieval tapestry, please join me at The Cloisters this Sunday, February 3, for “Birds, Beasts, and Flowers.” We’ll meet in the Main Hall at noon and spend an hour in the galleries. The program will repeat at 2:00 p.m. For more on gallery talks, programs, and events at the Museum, see Events at the Cloisters.

???Deirdre Larkin