|

|

|

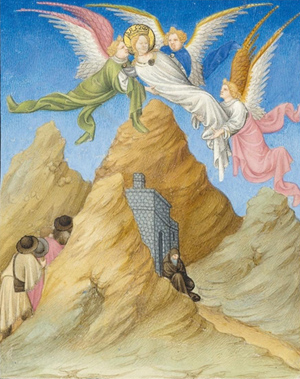

Above: Details of illuminations from Folio 15r, Folio 17r, and Folio 19v from the Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry, 1405–1408/9. Herman, Paul, and Jean de Limbourg (Franco-Netherlandish, active in France by 1399–1416). French; Made in Paris. Ink, tempera, and gold leaf on vellum; 9 3/8 x 6 5/8 in. (23.8 x 16.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1).

Every book of hours is unique in some way. What makes the Belles Heures unique is the addition of seven “picture book” cycles. Unlike the texts traditional to books of hours, these are not prayers or other devotional writing, but highly abbreviated narratives—stories about saints and sacred history. The texts are shortened versions of stories mostly taken from The Golden Legend, a popular collection of saints’ lives dating to the thirteenth century. But while the texts are abbreviated, the illustrations in the Belles Heures are not. In one sense, they’re like children’s picture books in that they have a succession of richly detailed painted images with only a few lines of text per page. The picture book cycles seem to have been added to the manuscript after the traditional sections were completed, to showcase the Limbourg brothers’ talents as artists, and to give Jean de Berry more action pictures to enjoy.

The first of the picture book cycles, immediately following the calendar, is the story of Saint Catherine of Alexandria. Although it appears early in the manuscript, it was probably among the last sections to be painted. Every page has a full-page illumination, with only four lines of text at the bottom in alternating blue and red ink, which matches the format of all the later added cycles and is unlike the two-column text format of the book’s original elements. It is also self-contained in an independent quire that was inserted into the manuscript.

Saint Catherine’s story would have appealed to Jean de Berry because of her royal lineage, her beauty, her intelligence, and her faith. The duke owned several of her relics and she was a patron saint of his second wife (Jeanne de Boulogne) and of the University of Paris. Catherine is prominent in the representation of saints adoring the Virgin on Folio 218r in the manuscript. She is presented as a Christian scholar who resists idolatry and the arguments of pagan philosophers and is punished with imprisonment and torture before being beheaded. The cycle closes with an image of her body being carried to Mount Sinai, where an important monastery was dedicated to her in the sixth century.

Illumination from Folio 17v

One of the most beautiful and complex scenes in this section is Folio 17v, Saint Catherine Tended by Angels. Here is Catherine at her loveliest, seated and semi-nude but still bearing her royal crown, submitting to the ministrations of three angels. Although they appear to apply salve, no wounds appear on Catherine’s unblemished body, presented for the viewer’s delectation. We see Catherine within the building, but also see the Empress Faustina and the jailer outside. The text says they see Catherine “in a wondrous light,” a phrase conveyed with the brilliance of white circling her figure in the drapery and wings of the angels. Unlike Folio 16v, where the building is shown full height, creating an absurd disjunction of scale and forcing the monumental Catherine to be squashed into the entrance, the building here is cut off by the lower frame of the picture, and we are permitted to zoom into the drama. The text indicates that the empress converted to the Christian faith after having discoursed all night with Catherine on “the rewards of eternal life.” The image captures the moment of surprise and discovery of Catherine’s divine assistance; the text fills in the detail of the narrative to explain the Empress’s execution in the following illumination (Folio 18r).

Illumination from Folio 20r

Two of the following pages (Folio 18v and Folio 19r) are among the most graphically violent in the manuscript, but the other image that is truly remarkable is the final one in the cycle. Folio 20r, Angels Carry the body of Saint Catherine to Mount Sinai, concludes Catherine’s story with her body wrapped in a shroud and carried by angels to her monastery. It conflates time by presenting in one scene the arrival of her remains (fourth century), the fully constructed monastery (built in the reign of Justinian, 527–565), and medieval pilgrims—perhaps contemporaries of the duke—visiting the site in Sinai. It also shifts scale, with the pilgrims as large as the massive stone monastery and Catherine largest of all, yet it is perfectly clear in what is represented. It brings a final miracle to provide closure to the story.

|

|

|

Details of illuminations from Folio 22r, Folio 23r, and Folio 24r

Following the Saint Catherine story and before the next major section of the manuscript are some texts that are more traditional to books of hours. Written in the two-column black ink of the traditional sections, Folios 21 through 29 were likely among the first pages in the manuscript to be written and illuminated, and feature only quarter-page paintings. They comprise readings from the Gospels and two prayers to the Virgin. Three of the Gospel readings are introduced by “portraits” of their evangelists together with their symbols (Man or angel for Matthew, Ox for Luke, Lion for Mark), but at least one page was lost, which would have contained the image of John and the start of his text. The readings were meant to accompany major feasts of the Church, and are found in most fifteenth-century books of hours.

Two illuminations from Folio 26v

Also to be found in many books of hours are the two Latin prayers to the Virgin that follow, known by their opening words as Obsecro Te and O Intemerata. The latter prayer begins on Folio 26v, which also includes two quarter-page paintings comprising one scene. The prayer extols the Virgin and asks for forgiveness of sins; the illumination technically has nothing to do with the text. Known as the Ara Coeli, it shows the vision of the Virgin as pointed out to the Roman Emperor Augustus by the Tiburtine Sibyl. Augustus and the Sibyl are nowhere mentioned in the prayer. Although the image is therefore not an illustration of the prayer, the emperor at his prie-dieu with his open prayer book can be understood as a royal stand-in for Jean de Berry himself with his book of hours, praying to the Virgin with the prayer O Intemerata as written in the page. In this way the image can function as a mirror for the reader and as an inspiration to contemplation. This is a theme we will visit again and again as we leaf through the manuscript.

—Wendy A. Stein

Tags: Saint Catherine

March 18, 2010 at 6:03 PM

I enjoyed learning about Saint Catherin and looking at the beautiful illuminations. Thank you so much for sharing. I plan to subscribe to this blog.

March 19, 2010 at 12:13 PM

Thank you, Joy, for your support. I am glad you enjoyed looking at the illuminations and welcome your subscription – please let me know if you have any questions!

Wendy

March 20, 2010 at 7:32 AM

Congratulations for the spectacular documentation on the website of MET.

Since many years I have a book with the reproduction of the miniatures, but now I can have a better idea of the originals.

By the way, I think it’s very interesting to observe that the Christians of ancient Alexandria elaborated the idea of the mechanic wheel not as a tool of progress but as a tool of the Devil.

Best regards

March 21, 2010 at 8:58 PM

Were there any special techniques used in rendering such small works of art. In plain words, how do you see to paint so small.

Thank you.

ML Russell

March 22, 2010 at 11:59 AM

Thanks to Giorgio and Mary Lou for your comments and questions.

The wheel was meant to be an effective instrument of torture for the Roman emperor to use against Catherine—in fact it was meant to be four wheels between which she would be torn apart. I suppose you could say the idea was a mechanical innovation, even though it didn’t work. As for a tool of the devil—in Christian theology, the prevention of martyrdom is more likely to be viewed as the work of the devil than the instrument of martyrdom.

As to the question of the miraculously small—how it is possible to get such wondrous detail into these tiny pictures. My favorite comment came from a friend who visited the exhibition; Enzo said, “It is as though they pulled out one eyelash and then painted with it!” We all are amazed at this skill. I cannot fully explain it, but remember that the Limbourg brothers were in their late teens and early twenties, and so had sharp eyes. In addition, eyeglasses and magnifying glasses were known by this period, and in some form were likely used. Even so, it is a marvel. For those who see the exhibition here at the Museum, you can see a few huge banners that blow up a page to the size of the wall, proof of the inherent monumentality packed into these tiny images.

May 14, 2010 at 7:35 AM

Thank you for this wonderful blog! I’ve been studying abroad and I really hope that the exhibit isn’t over by the time I get back home.

I have one question: what is the meaning of the abstract backgrounds in the illuminations of Saint Catherine’s torture? Are they meant to thematically link the images or are they simply random?

Thank you,

Ceci

May 14, 2010 at 12:57 PM

Dear Ceci,

Thanks for your comment and for following this blog from abroad. The exhibition will close on June 13, and I know many study abroad programs will be done by that time, so I hope you will be able to come in. There is nothing like seeing the pages in the original, especially if you use one of the wonderful magnifying glasses we have available in the gallery.

I believe the abstract patterned backgrounds on most of the pages in the Catherine cycle do not have an iconographic or thematic meaning. They continue an old tradition of tessellated backgrounds found in many earlier manuscripts, especially from the thirteenth century on. One scholar found that the patterned backgrounds gave focus to the narrative, but I do not really agree. I am currently working on a post that will mention the co-existence in the Belles Heures of pages with these backgrounds and others that have blue sky. That discussion will be part of the post on Saint Jerome, to be published next Wednesday, May 19.

Wendy

June 30, 2010 at 6:05 AM

Catherine is depicted reading (silent learning of something written by others), being tortured and being saved, but her most important act was going to court and convincing the emperor’s philosophers to become christians. The debate or dispute, although known and told, was very rarely highlighted in pictures, a way of teaching everybody could understand and was used to teach illiterate people (most of the population in fact). I wonder if there is such a scene painted in this manuscript.

Probably a woman reader or patron would have liked it but may be not a man as it questioned the stablished position of women in society as subordinate individuals.

30 June 2010

July 1, 2010 at 3:20 PM

Dear Nieves,

Thank you for your interesting comment and engagement with the story of Saint Catherine. The scene you describe, where Catherine out-argues the scholars, and converts them to Christianity, is indeed in the Belles Heures. You can see it on Folio 16r, right at this site, in the “Manuscript Pages” section. When I began to read your question, I thought you were going to ask about the mystic marriage of Saint Catherine to Christ, a scene often depicted in art, but absent from the Catherine cycle in the Belles Heures.

Wendy

July 2, 2010 at 4:09 AM

The Mystic marriage belongs to the life of St. Catherine of SIENA, an altogether different saint, that is why you cannot find them here.

Thanks for the picture I had missed.

Nieves

July 2, 2010 at 10:05 AM

Thank you, Nieves, for the correction. You are absolutely right about Catherine of Siena, of course.

Wendy

August 5, 2010 at 6:15 AM

Dear Wendy and Nieves,

You were both right actually:

I am pretty sure that both Saint Catherines had “Mystical / Spiritual Marriages” to Christ. In the Golden Legend it is related that St Catherine of Alexandria “married” Christ:

“Then our Blessed Lord took up, his mother and said: Mother, that which pleaseth you, pleaseth me, and your desire is mine, for I desire that she be knit to me by marriage among all the virgins of the earth. And said to her Katherine, come hither to me. [...] And there our Lord espoused her in joining himself to her by spiritual marriage, promising ever to keep her in all her life in this world, and after this life to reign perpetually in his bliss, and in token of this set a ring on her finger, which he commanded her to keep in remembrance of this [...]. (Extract from the Golden Legend, Life of St Katherine of Alexandria)

And the much later saint, St Catherine of Siena had a vision of Christ and experienced a “Mystical Marriage” in c1366.

Regards,

Charlotte

August 5, 2010 at 2:22 PM

Many thanks to you, Charlotte, for your wisdom and clarification.

Wendy