|

|

|

Above: Details of illuminations from Folio 158r, Folio 163v, and Folio 173r from the Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry, 1405???1408/9. Herman, Paul, and Jean de Limbourg (Franco-Netherlandish, active in France by 1399???1416). French; Made in Paris. Ink, tempera, and gold leaf on vellum; 9 3/8 x 6 5/8 in. (23.8 x 16.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1).

This section of the manuscript contains a microcosm of all the complexity of structure and variety of book design to be found in the Belles Heures. It is a traditional section, yet embedded within it is an added picture-book cycle. It is inconsistent in the level of decoration accorded the various saints: some get no picture, while others get quarter-page or full-page illuminations. The border treatments also vary between narrow and broad bands. It includes stories told in single climactic scenes as well as simple, standing “portraits” of individual saints. In this section, we witness the Belles Heures in transition between a traditional book of hours and the exceptional work it became.

Most books of hours have a selection of suffrages???brief prayers and invocations to holy persons or concepts. Depending on the cost and luxury of the manuscript, there may be only a few of these memorials, or there may be more than a hundred; similarly they may include only one illumination for the group, or a picture for every saint. In the Belles Heures there are fifty-six suffrages, graced with fourteen full-page and twenty-seven quarter-page illuminations. Unlike some other lavish books of hours, in which we have a sense of a firm plan for book design, variety reigns here, and a true internal shift in layout can be discerned.

Illumination from Folio 157r

We can see clearly that this section began with a traditional layout; its pages were ruled for two columns of black script. All of the suffrages or memorials are written in this way. One of the first memorials (Folio 157r) honors the Cross and is marked by a full-page illumination of the cross on an altar, adored by princely figures, with a few lines of text in black ink and two columns beneath. Interestingly, this traditional layout follows two nontraditional folios (Folio 156r and Folio 156v) that feature full-page pictures of Heraclius and the True Cross. We may presume that the artists created 157r first, which means that within these three pages we are witnessing one of the moments in which the book design switched???when patron and artists moved out from tradition to innovation, where the decision was taken to expand the opportunity for story telling by inserting a picture-book cycle with four single-column lines of text in alternating red and blue, even though the page had been ruled for two columns. In addition to the narrative they depict, these three folios tell a story about the creation of the book itself.

Illumination from Folio 156r

Heraclius was the great Byzantine emperor of the seventh century who recovered the True Cross from the Persians and returned it to Jerusalem, a story recounted in The Golden Legend. Folio 156r shows Heraclius grandly riding with the cross in a splendid carriage, a composition echoed in a bronze medal on view in the exhibition. It is possible that both the medal and the page were designed by the Limbourg brothers, or that one was copied from the other; in any case, we have a sense here of the Limbourgs as court artists, working with access to the duke’s collections in a variety of media. Looking again at the page, we see that the gates to Jerusalem are closing as the carriage nears: Heraclius is not allowed to enter in such a grand fashion.

Illumination from Folio 156v

On Folio 156v, we see Heraclius, dismounted from his chariot, more humbly dressed, and carrying the cross on his back, with the gates of Jerusalem now open to receive emperor and cross.

Among the many other illuminations of specific saints in this section, I’ll highlight only a handful of my favorites this week, and return to the section for more illuminations in the next post. (Remember, you can browse through all of them???and enlarge them to see the amazing detail???in the Manuscript Pages section.)

Illumination from Folio 164v

Saint Eustace (Folio 164v), a Roman soldier who was exiled after he converted to Christianity, was traveling with his sons when he came to a river. He carried one son across and was on his way to get the other when each boy was abducted by a wild beast???one by a lion and the other by a wolf. Here Eustace is shown lamenting in mid-stream, unaware that his Christian faith will ultimately reunite him with his loved ones.

Illumination from Folio 167r

Saint George and the Dragon (Folio 167r) is one of the most familiar scenes in this section. The heroic knight in shining armor, rescuing a damsel in distress from the dreaded monster, hits all the buttons of medieval clich??. The Limbourg brothers nevertheless enliven the scene with idiosyncratic details. I especially like the dragon babies, emerging from their cave in distress at the fate of their mommy, and the way the angel takes on the duties of a feudal page, holding the saint’s helmet for him.

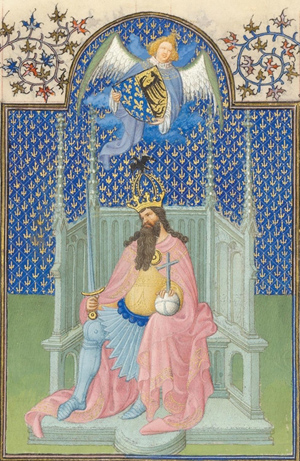

Illumination from Folio 174r

Charlemagne (Folio 174r) sits regally on his elaborate throne, a majestic figure in a composition very different from all the other saints. His coat of arms includes the fleur-de-lis of France along with the imperial eagle of the Holy Roman Empire; their equal billing stresses the independent descent of the French royal family from Charlemagne’s line. (See “The Garden in Heraldry” on The Medieval Garden Enclosed blog for more about coats of arms and the fleur-de-lis, in particular.) This massive kingly figure reminds me of a work of art in a very different medium and scale: the Heroes Tapestries at The Cloisters. That ensemble is among the oldest tapestries in the Museum’s collection, was certainly known to Jean de Berry and may have been in his collection or in that of another member of his royal family.

|

|

Illuminations from Folio 170r and Folio 168r

Two of the saints in the suffrages section are shown working weather miracles. Saint Anthony of Padua (Folio 170r) is shown preaching outdoors when a devil sent a storm to disrupt the proceedings. Anthony admonished the listeners not to flee, and raised his hand in benediction, sending the storm away. We can see the devil fleeing in the upper right corner, taking his darkness, thunderbolt, and hail with him. Saint Nicholas (Folio 168r) saved seafarers who were panicking in a storm that had already broken the mast of their ship. While some were reaching for lifeboats in despair, others called on the saint, who grasped the mast to steady the boat. Look at the sky to the left: where Nicholas has already been, he has cleared the storm, while on the right, amazingly free brushstrokes create the dark turbulence of the tempest. The frothy sea is painted with silver, which is preserved under a clear glaze.

Illumination from Folio 162v

Even the saints recognized only with a quarter-page illumination can be outstanding. The Limbourg brothers were capable of demonstrating their narrative power in an incredibly small compass. The scene of the martyrdom of Saint Lawrence (Folio 162v) is packed with eleven figures, a raging fire, a mountainous landscape, and a blue firmament, all within a space measuring close to 1 x 3 inches. The nude saint is chained to a grill, while a man in blue plies bellows to stoke the fire beneath, as a king and his entourage look on, and God blesses the scene from above. Once again, this manuscript astonishes with its miracles in miniature.

We have only begun to look at this section of the manuscript. Next week I will take on a few more saints, and also pose the question: Is the Belles Heures a violent book?

???Wendy A. Stein

Tags: Byzantine, Charlemagne, dragon, fleur-de-lis, Heraclius, Heroes Tapestries, Saint Anthony of Padua, Saint Eustace, Saint George, Saint Lawrence, Saint Nicholas, saints, suffrages, True Cross