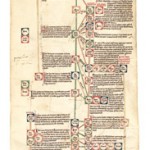

Above: The Compendium of History through the Genealogy of Christ (detail). Peter of Poitiers. England, 13th century. Anonymous Lender.

Many histories written in the Middle Ages include the hand of God in the workings of historical events. Certainly a Compendium roll shown in the exhibition (see detail above) and another at The Cloisters fit this model. The history of the world it presents is organized around what its Christian author would have considered the inevitable and culminating event of the birth of Christ.

Today’s historians may regard such a history with bemusement or derision, but setting aside the religious nature of its content, this compendium offers many topics for discussion. In several ways, it has features that are actually quite modern???indeed, so modern that we may not realize the degree to which they were medieval innovations. The first such feature is the way in which the Compendium divides the history of the world into epochs. The pictures that appear at regular intervals along the central stemma, or scroll, are there primarily as visual cues to indicate the beginning of a new epoch???the ages of Adam, of Noah, of Abraham, of King David. Contemporary scholars and historians are just as keen as medieval historians to label and describe epochs: the Renaissance; the Enlightenment; the Jazz Age; the post-war era; the Sixties. These efforts to organize time into ages or eras, to understand an era as having a set of qualities that distinguish it from another, find their roots in the medieval historical enterprise.

The fascinating system of parallel and intersecting lines found on the Compendium roll speaks to a second noteworthy feature of medieval history-writing: the wish to collate historical events from different places into a single framework. It shows how biblical history synchronizes with the political histories of ancient Syria, Assyria, Babylon, Persia, Greece, and Rome. The great encyclopedist Isidore of Seville developed this very idea in the seventh century. I marvel at the ambitions of medieval historians who aimed to present a comprehensive view of time, from the beginning of creation and across the known world. The Metropolitan Museum???s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History is a twenty-first century example of just such an all-encompassing history, which also divides time into discrete chronological segments. What happens to our sense of present and future when we impose such a scheme on the past?

???Melanie Holcomb

Tags: compendium, Isidore of Seville

June 13, 2009 at 9:49 pm

As an avid reader of art history, I find it very plausable that religious magistrates would be the first to consolidate public affairs and attitudes into epochs. With that said, I now believe that they too were probably some of the first art historians, because religious institutions were often given or purchased many fine pieces of art and decor. Religious magistrates might have just combined their love for chronicalization with their immediate surroundings found in chapels, or cathedrals throughout the world to produce records describing the progression of art.

June 26, 2009 at 6:59 pm

Dear Tiffany,

I am not sure whom precisely you mean by religious magistrates, but it is true that monasteries and churches often catalogued their collections of books and liturigical objects. The language of these inventories is generally quite spare, but they can give a sense of how art objects were categorized and what were considered their distinguishing features. Also, there are chronicles and other kinds of writing that might list objects given to an institution by a particular individual or at a particular moment as well as the occasional text describing the history of a particular site or building. Still, I have a hard time coming up with anything in the writings I know from the Middle Ages that would approximate some kind of art history. I’m not sure it’s a genre that coincided with medieval concerns. Perhaps someone else knows of some medieval texts that would suggest otherwise?