|

|

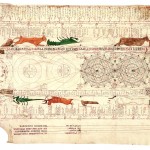

Above, from left to right: Jean Pucelle (active ca. 1320–1324), Saint Louis Feeding the Sick (detail), From The Book of Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, Paris, France, 1324–28, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.2); Opicinus de Canistris (1296–ca. 1354), Diagram with Zodiac Symbols (detail), Avignon, France, 1335–50, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City, Pal. Lat. 1993.

Often when I view medieval manuscripts I become so focused on the words and pictures adorning the pages that I forget to take note of the materials with which they were created. Yet after traveling through this exhibition, it becomes strikingly evident that the materials themselves—the parchment and ink—are as important as the narratives they contain.

Parchment was the primary support employed by medieval scribes to preserve their written words. Its use extends as far back as the fifth century B.C. According to the great Roman historian Pliny, the material was invented in Pergamum (the Latin word for “parchment” is pergamenum) in the second century B.C., after the exportation of papyrus from Alexandria was halted. Paper—which was invented in China during the second century B.C.—would not become widely used in Europe until the twelfth century A.D.

Like leather, parchment is manufactured from animal hides, but it differs from leather in the way it’s produced and treated. Parchment is stretched, scraped, and dried, while leather is tanned—a process that involves adding vegetable tannins to the skin to chemically alter its physical properties. A quick glance at the exhibition’s earliest manuscripts, like the pages from the ninth-century Corbie Psalter, reveals parchment’s amazingly durable nature.

The two words “parchment” and “vellum” are often used interchangeably. Both materials come from animal hides, but the distinction between them may be made clear through etymology: “vellum” comes from the Latin vitulinum, meaning “veal” or “calf.” Parchment, on the other hand, may be made from the skin of a sheep or a goat. Apart from the linguistic distinctions, a well-trained conservator’s eye is able tell the difference between the two materials due to the hair patterns still evident in the surface of the skins.

One particular manuscript in our exhibition, The Book of Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux (see image above, at left), is made from a type of parchment called slunk. The finest form of parchment, slunk was taken from the hides of stillborn calves. The pages of this text are buttery smooth and paper thin, lacking any marring or imperfections. (Hanging on the opposite wall in the exhibition galleries is a small sketch that represents the other extreme; its parchment appears thick, dirty, and worn, as if it had been crumpled and then smoothed into a frame.)

It was not until I saw the folios of Opicinus de Canistris, the eccentric cleric working in the papal court of Avignon, in relation to the other manuscripts of the exhibition that I grasped the enormity of labor and expense that went into the production of a medieval manuscript. Opicinus utilized entire untrimmed sheets of parchment, which still retain the original shape of the goats from which they were made (see image above, right). On average, one animal skin could yield two to three bifolia, which would produce eight to twelve pages for decoration. Of course, the number of pages depended on the size of the book. A text like the Salomon Glossaries, the largest book in the show, most likely required one animal per bifolium. This 229-folio book required 115 bifolia, or roughly 115 individual animal hides. We can see that the resources required to make one medieval manuscript were exorbitant—from the hundreds of animals required to make the pages to the often exotic minerals ground for the scribes’ ink palette. (All parts of the animal were utilized, from the meat to feed the local people to the hooves for glue.)

Unlike painting, which seeks to obscure as much of the substrate as possible, medieval drawings reveal the scribe’s line as a chisel, portioning off areas of raw parchment to hew figures. In many respects, I see parchment as the primary material here, with the inked lines as accessory tools involved in the craft.

—Eric R. Hupe, Exhibition Intern

Tags: Jeanne d'Evreux, Opicinus de Canistris, parchment, pergamenum, pergamum, Salomon Glossaries, vellum

July 9, 2009 at 8:45 am

Eric,

A friend of mine recently attended your tour of the Pen and Parchment exhibit and raved about your presentation. Now I would like to hear it for myself. Can you tell me when you will conducting another tour of the exhibit?

July 13, 2009 at 9:49 am

Bob,

The next gallery talk for this exhibition is July 16 at 11am.

July 14, 2009 at 12:12 pm

Dear Bob,

Thank you for your kind words. I am flattered, and most importantly happy that your friend enjoyed her time at the exhibition. Unfortunately, as of now I am not scheduled to give another gallery talk. However, the next talk will be given by the exhibition’s curator, Melanie Holcomb, on July 16th at 11:00am. If you cannot attend that session there are others to choose from just check the museum’s calendar.

(This link should direct you to the Pen and Parchment section of the calendar: http://www.metmuseum.org/search/iquery.asp?c0=t:8//:ssl//sitemap%20taxonomy//:Calendar:&c1=dt:8//eventStartDate//:gte//2009..06..09&command=text&attr1=penparchment&t=0&w=on&domains=general:sitemap%20id)

I hope you make it to the galleries and thanks again.

All my best,

Eric

July 17, 2009 at 4:11 pm

Parchment was used more than 1000 year BC.

Vellum can also be made also from goat and sheep.

Parchment can be made from the skin of many animals, also from calf.

Vellum is used by Englishmen. And mu experience is that they do not know a difference with parchment.

In the rest of the world ‘parchment’ is used for this material.

Pliny cited Varro. May be in a wrong way.

And the etymology of parchment?

The difficult is to see the difference between goat and sheep.

July 21, 2009 at 12:32 pm

Dear Henk de groo,

You raise many interesting points about parchment. There is indeed evidence of parchment being employed as far back as 1000 years BC; however it does not take hold as a primary writing substrate until the second century BC. As for as the distinction between vellum and parchment, today the two are now considered to be almost synonymous, even though vellum traditionally only refers to parchment made of calf. In fact many scholars nowadays refrain from using both words and instead refer to the material as “membrane.” For more information on parchment and the process of making it, I can refer you to two decent websites. The Getty’s exhibition website The Making of the Medieval Book features videos of the process and a website from the Central European University offers a more detailed textual description of parchment and its history.

Getty

Central European University

All the best,

Eric