Archive for the ‘Food and Beverage Plants’ Category

Wednesday, December 18, 2013

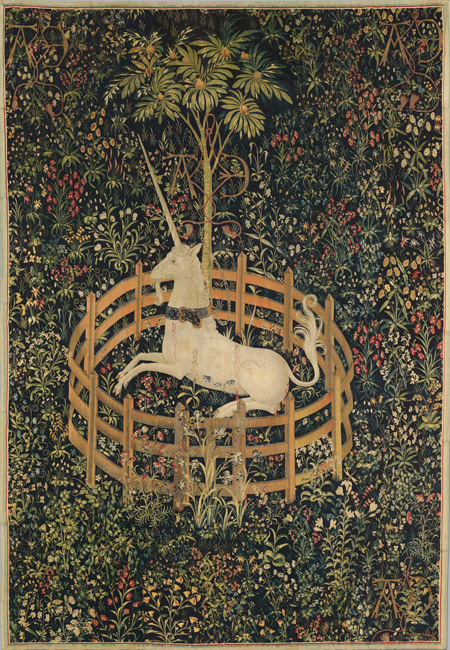

Detail of hazel tree in The Unicorn is Killed and Brought to the Castle (from the Unicorn Tapestries), 1495–1505. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1937 (37.80.5)

The common hazel, or Corylus avellana, is an understory tree native to Europe and western Asia and is widely distributed from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean. The English name for the tree is derived from the Anglos-Saxon word haesel. The hazel appears in two critical medieval horticultural sources, the Carolingian Capitulare de Villis and in the St. Gall Plan, along with references in folklore, literature, and both Pagan and Christian traditions. The hazel is still cultivated today for its nuts, which are harvested after they have fallen from the tree in autumn. Hazelnuts are commercially grown in Oregon and Washington, although Turkey exports 75% of the world’s supply. Read more »

Tags: hazel, Unicorn tapestries

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, Magical Plants, Medicinal Plants, Plants in Medieval Art | Comments (1)

Thursday, June 13, 2013

It is June, it is June,

the pomegranates are in flower,

the peasants are bending cutting the bearded wheat.

The pomegranates are in flower

beside the high road, past the deathly dust,

and even the sea is silent in the sun.

Short gasps of flame in the green of night, way off

the pomegranates are in flower,

small red flowers in the night of leaves.

And noon is suddenly dark, is lustrous, is silent and dark

men are unseen, beneath the shading hats;

only, from out the foliage of the secret loins

red flamelets here and there reveal

a man, a woman there.

???Andraitx???Pomegranate Flowers, by D.H. Lawrence

From left to right: The vivid scarlet blossoms of a potted dwarf pomegranate tree in full flower glow against the gray stone of the blind arcade in Bonnefont garden; detail of pomegranate flowers. Both dwarf and standard forms of pomegranate are grown here. Although cultivated for hundreds of years, the dwarf form is not medieval, but it lends itself to pot culture, and can be more easily managed than the full-sized tree. Photographs by Carly Still

Although these photographs were taken just a few days ago on a gray day in Bonnefont garden, this post is coming from sunny California, where I am participating in a panel discussion on museums and gardens at the Getty Center in conjunction with an exhibition curated by Bryan Keene. Read more »

Tags: bay, fig, laurel, olive, pomegranate

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, Gardening at The Cloisters | Comments (6)

Friday, May 24, 2013

Left: Angelica silhouetted against the blind arcade in Bonnefont cloister. Modern gardeners admire the bold, architectural qualities of angelica as an ornamental plant, but it has a long history as a useful herb. Right: The flower structure is typical of the carrot family to which it belongs. Photographs by Carly Still

Unknown to the Greeks and Romans, the beautifully named Angelica archangelica is a native of northern Europe. It can be difficult to determine whether it is this “garden angelica” or its close relative, A. sylvestris, that is under discussion in early sources, although Renaissance plantsmen like John Gerard distinguished between the two (see images of A. sylvestris in the wild).

Read more »

Tags: angelica, Angelica archangelica, Angelica sylvestris, asafoetida, carrot, parsley

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, Gardening at The Cloisters, Medicinal Plants | Comments (0)

Tuesday, December 18, 2012

Above, left: The holiday decorations at The Cloisters are made by hand from plants linked with the celebration of Christmastide in the Middle Ages. A sheaf of wheat???an allusion to the eucharistic symbolism of the “altar-manger” and the transformation of the Christ Child into the bread of the Mass???stands near the altar frontal in Langon Chapel. Right: In the central panel of Gerard David’s triptych Nativity with Donors and Saints Jerome and Leonard, the wheat ears that fill the manger and spill from the sheaf in the foreground are shown in meticulous detail.

A strong link was made between wheat and the Nativity early in the history of Christian exegesis, based on the symbolism of the Eucharist. The identification was founded in the interpretation of such scriptural passages as John 6:41, in which Jesus identifies himself as “the bread come down from heaven.” In his homily on the Nativity, Homilia VIII in die Natalis Domini, the sixth-century Doctor of the Church, Saint Gregory the Great, translated “Bethlehem” as “house of bread” and expounded the transformation of the Christ Child from hay into wheat. These interpretations???as well as the practice of placing consecrated bread in the relic of the Holy Crib installed at the church of Santa Maria Maggiore and the liturgical manger plays that originated there and were revived and popularized by Saint Francis of Assisi???emphasized the sacramental aspect of the birth of Christ. The pictorial tradition of showing the infant Jesus lying on a heap of grain is found in representations of the Nativity from the end of the fifteenth century. As Maryan Ainsworth notes, the composition of the central panel in Gerard David’s early sixteenth-century triptych, in which Mary and Joseph adore the Christ Child, owes something to the Nativity by Hugo van Der Goes (see image) in the Gem??ldegalerie in Berlin, painted about 1480. For a list of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Italian paintings with similar iconography, see Mirella D’Ancona Levi.

???Deirdre Larkin

Sources:

Ainsworth, Maryan W. Gerard David: Purity of Vision in an Age of Transition. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998.

Levi D’Ancona, Mirella. The Garden of the Renaissance: Botanical Symbolism in Italian Painting. Firenze: L. S. Olschki, 1977.

Schiller, Gertrud. Iconography of Christian Art. Translated by Janet Seligman. Vol. 1. Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1971.

Tags: altar, bread, Christmas, Christmastide, eucharist, Jesus, manger, nativity, sheaf, wheat

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, Medieval Agriculture, The Medieval Calendar | Comments (1)

Thursday, October 4, 2012

From right to left: A small start of wild or creeping thyme, a native of Northern Europe, in a terra rossa pot; detail of a planting of common or garden thyme, indigenous to the Western Mediterranean, growing in a sunny bed under the parapet wall in Bonnefont cloister. Although these two plants are easily distinguished in the garden, it can be difficult to know which of several species of thyme is under discussion in ancient and medieval sources.

There are hundreds of?? species in the genus Thymus, and a large and confusing array of hybrids and cultivated forms.??Ancient and medieval sources agree on the heating and drying properties of thyme, which is still greatly valued for its antibacterial and antifungal properties, but the species known in the European Middle Ages were not those of the ancients. The attempt to equate the plants discussed by Dioscorides in the De Materia Medica with more familiar species would occupy botanists well into the Renaissance.

Read more »

Tags: Dioscorides, Hildegard of Bingen, Pliny, thyme

Posted in Botany for Gardeners, Food and Beverage Plants, Fragrant Plants, Gardening at The Cloisters, Medicinal Plants | Comments (1)

Friday, September 21, 2012

The blue-green fronds of rue were admired for their beauty in the Middle Ages, and the intensely aromatic leaves were prized as a condiment, a medicament, and an amulet.?? Photograph by Carly Still

Here is a shadowed grove which takes its color

From the miniature forest of glaucous rue.

Through its small leaves and short umbels which rise

Like clusters of spears it sends the wind???s breath

And the sun’s rays down to its roots below.

Touch it but gently and it yields a heavy

Fragrance. Many a healing power it has ???

Especially, they say, to combat

Hidden toxin and to expel from the bowels

The invading forces of noxious poison.

???Hortulus, Walahfrid Strabo, translated by Raef Payne

Read more »

Tags: Anethum graveolens, Apicius, Apium graveolens, bitter, Capitulare de Villis, Dioscorides, Hildegard of Bingen, Hortulus, Mithridates VI, mithridatum, phytodermatitis, Pliny, rue, Ruta graveolens, St. Gall, Tacuinum Sanitatis, Walahfrid Strabo

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, Fragrant Plants, Gardening at The Cloisters, Magical Plants, Medicinal Plants | Comments (0)

Friday, September 14, 2012

Unlike many of its relatives in the Asteraceae, or daisy family,??the golden disk flower of tansy is not surrounded by ray petals.??Although both the flowers and leaves are intensely bitter, tansy has a long history as a culinary herb.??

Tansy (reynfan) is hot and a bit moist, and is effective against all over-abundant humors which flow out. Whosoever has catarrh, and coughs because of it, should eat tansy, taken either in broth or small tarts, or with meat, or any other way. It checks the increase of the humors, and they vanish . . . .

???Hildegard of Bingen,??Physica,??Chapter CXI

The old German name reynfan used by Hildegard refers to the effect of tansy (Tanacetum vulgare) on the “reins,” or kidneys. The fifteenth-century herbal??Der Gart der Gesundheit differs from Hildegard in classifying tansy as hot and dry in the first degree, rather than moist; it recommends tansy as a diuretic and vermifuge, as well as a treatment for gout and fever. (For more on Hildegard of Bingen, see “Mutter Natur,” October 15, 2010. For more on the humoral theory on which her prescription is based, see “Cool, Cooler, Coolest,” July 27, 2012.) Read more »

Tags: Bonnefont Garden, daisy, Hildegard of Bingen, John Gerard, reynfan, Tanacetum, tansy, Walahfrid Strabo

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, Gardening at The Cloisters, Medicinal Plants, The Medieval Garden | Comments (0)

Friday, August 3, 2012

Sesame, also known as “benne,” is a tender, large-leaved, Asian annual grown here in Bonnefont garden. Sesame has been cultivated for some five thousand years and was known to many cultures in antiquity. Although the plant is somewhat rangy and coarse in habit, the tubular flower (above, left) is attractive. The immature green pods (above, right), which will split and spill out their seeds when ripe, contain one of the world’s oldest domesticated oilseeds. The seeds also have a long history of use as a seasoning.??Photographs by Carly Still.

A cultivated plant of fabulous antiquity, sesame (Sesamum indicum) is known as simsim in Arabic, susam in Turkish, sesam in German, s??same in French, sesamo in Italian, and sesame in Spanish. Called sesemt by the ancient Egyptians, it was also grown in Ethiopia in very early times. Sesame seeds were taken from West Africa to America by slave traders; the name “benne” derives from the West African benni. Sesame had long been grown in India and Persia, and was introduced to China by the end of the fifth century A.D. Read more »

Tags: De Materia Medica, Dioscorides, flax, hellebore, Herodotus, Hortus Sanitatis, John Ruskin, poppy, sesame, Sesamum indicum

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, Medicinal Plants | Comments (0)

Friday, May 25, 2012

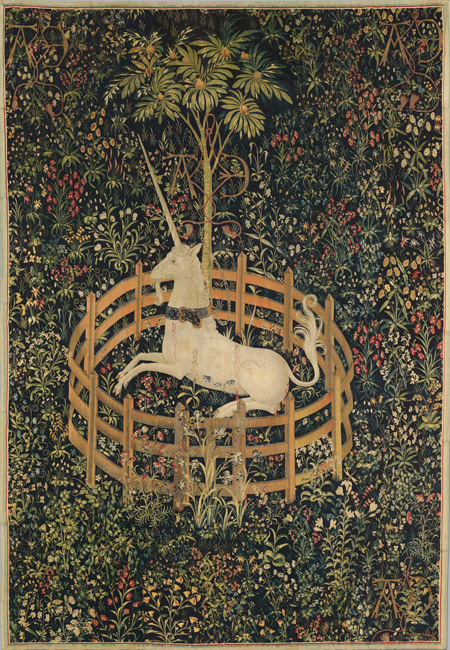

The Unicorn in Captivity, 1495???1505. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1937 (37.80.6). The profusion of flowering plants that springs from the millefleurs meadow on which the unicorn rests includes both garden plants and wildflowers. An iris and a clove pink are prominently placed outside the unicorn’s enclosure; both were intensively cultivated in the Middle Ages, but the purple orchis silhouetted against the unicorn’s body depends on a special relationship with microorganisms in its native soil and would not have grown in gardens.

Roses, lilies, iris, violet, fennel, sage, rosemary, and many other aromatic herbs and flowers were prized for their beauty and fragrance, as well as their culinary and medicinal value, and were as much at home in the medieval pleasure garden as in the kitchen or physic garden. These plants were carefully cultivated, but many useful plants of the Middle Ages were found outside the garden walls, or admitted on sufferance.

Read more »

Tags: colewort, Fennel, gourd, herb, Hortulus, iris, kale, lamb's quarters, lettuce, lily, melon, nettle, poppy, pulse, purslane, rose, rosemary, sage, violet, Walahfrid Strabo

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, Fragrant Plants, Medicinal Plants, Plants in Medieval Art, Useful Plants | Comments (1)

Friday, February 3, 2012

The trees went to anoint a king over them: and they said to the olive tree: Reign thou over us

And it answered: Can I leave my fatness, which both gods and men make use of, to come to be promoted among the trees?

???Judges 9: 8-9, Douay-Rheims Bible

Olive oil provided fuel for sanctuary lamps throughout the Mediterranean world in antiquity and the Middle Ages, as well as holy oils for religious purposes. Above, left: A menorah flanked by two olive trees, as depicted in the Cervera Bible, recently on view at the Main Building. The brimming vessels?? used to fill the lamp appear at the top of the menorah. Right: A fifth-century standing lamp decorated with a cross; bronze lamps of this type were common in the early Byzantine world.

The olive was held to be the first of trees in both classical and biblical antiquity, prized above even the grapevine and the fig. A gift of the goddess Athena, the sacred olive symbolized the arts of peace and prosperity; the ruthless destruction of an enemy’s olive groves in wartime was held to be sacrilegious act. The Roman natural historian Pliny, writing in the first century A.D., attests that Athena’s olive was still venerated on the Athenian acropolis in his day (Historia naturalis, XVI 239???40). Although slow to bear, the tree is very long lived, surviving for hundreds of years. (The SpiceLines blog features an illustrated post about a Spanish olive estimated to be eighteen hundred years old.)

Read more »

Tags: chrism, drupe, glucoside, Hildegard of Bingen, Mediterranean, oil, oleaster, olive, Physica, Pliny, Tacuinum Sanitatis

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, Medicinal Plants, Plants in Medieval Art, Useful Plants | Comments (0)