Archive for the ‘The Medieval Calendar’ Category

Friday, May 3, 2013

This pretty yellow flower, gathered since the Middle Ages when “bringing in the May,” was known in Middle English by various names, including primerose, primerole, and cowslyppe. Photograph by Carly Still

Primula veris, literally the “first little one of spring,” was known in Middle English as prymerole and as prymerose, or “the first rose.” It was also known as cowslip, a name thought to be derived from “cow slop” or dung, perhaps because it grew in meadows and pastures where cattle grazed. The names prymerole and prymerose came from the Latin through Old French, and were shared with the cowslip’s relative, the common primrose (Primula vulgaris). As Geoffrey Grigson notes in his fascinating compendium of plant lore, The Englishman’s Flora, it can be very difficult to distinguish which of the two species is meant in early sources. Renaissance plantsmen like William Turner, John Gerard, and John Parkinson tried to clarify the confusion caused by the shared common names; as late as the eighteenth century, the great Swedish naturalist and taxonomist Carolus Linnaeus considered the cowslip, the common primrose, and the oxlip (Primula elatior; see image) to be forms of the same species.

Read more »

Tags: cowslip, cuckoo, primrose, Primula veris

Posted in Medicinal Plants, Plants in Medieval Art, The Medieval Calendar | Comments (0)

Tuesday, December 18, 2012

Above, left: The holiday decorations at The Cloisters are made by hand from plants linked with the celebration of Christmastide in the Middle Ages. A sheaf of wheat???an allusion to the eucharistic symbolism of the “altar-manger” and the transformation of the Christ Child into the bread of the Mass???stands near the altar frontal in Langon Chapel. Right: In the central panel of Gerard David’s triptych Nativity with Donors and Saints Jerome and Leonard, the wheat ears that fill the manger and spill from the sheaf in the foreground are shown in meticulous detail.

A strong link was made between wheat and the Nativity early in the history of Christian exegesis, based on the symbolism of the Eucharist. The identification was founded in the interpretation of such scriptural passages as John 6:41, in which Jesus identifies himself as “the bread come down from heaven.” In his homily on the Nativity, Homilia VIII in die Natalis Domini, the sixth-century Doctor of the Church, Saint Gregory the Great, translated “Bethlehem” as “house of bread” and expounded the transformation of the Christ Child from hay into wheat. These interpretations???as well as the practice of placing consecrated bread in the relic of the Holy Crib installed at the church of Santa Maria Maggiore and the liturgical manger plays that originated there and were revived and popularized by Saint Francis of Assisi???emphasized the sacramental aspect of the birth of Christ. The pictorial tradition of showing the infant Jesus lying on a heap of grain is found in representations of the Nativity from the end of the fifteenth century. As Maryan Ainsworth notes, the composition of the central panel in Gerard David’s early sixteenth-century triptych, in which Mary and Joseph adore the Christ Child, owes something to the Nativity by Hugo van Der Goes (see image) in the Gem??ldegalerie in Berlin, painted about 1480. For a list of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Italian paintings with similar iconography, see Mirella D’Ancona Levi.

???Deirdre Larkin

Sources:

Ainsworth, Maryan W. Gerard David: Purity of Vision in an Age of Transition. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998.

Levi D’Ancona, Mirella. The Garden of the Renaissance: Botanical Symbolism in Italian Painting. Firenze: L. S. Olschki, 1977.

Schiller, Gertrud. Iconography of Christian Art. Translated by Janet Seligman. Vol. 1. Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1971.

Tags: altar, bread, Christmas, Christmastide, eucharist, Jesus, manger, nativity, sheaf, wheat

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, Medieval Agriculture, The Medieval Calendar | Comments (1)

Thursday, December 15, 2011

Above, from left to right: Gardener Esme Webb carrying a trug of English holly; volunteer Nuala Outes putting berried holly branches into the arch over the postern gate entrance.

Visitors entering the Museum by the postern gate (the main entrance to The Cloisters) from now through the first week of January will pass under a great arch of holly, the plant most strongly associated with the medieval celebration of Christmastide. (For more on the medieval significance of this beautiful and beloved tree, see “The Holly and The Ivy,” December 18, 2008). The ceremonial placing of a beneficent plant above a doorway is an ancient practice common to many cultures and periods. (Four of the doorways in the Main Hall are adorned with arches of ivy, apples, hazelnuts, and rose hips; see “Decking the Halls: The Arches,” December 2, 2008.) Read more »

Tags: apple, Christmastide, dioecious, hazelnut, holly, ivy, rose hip

Posted in Gardening at The Cloisters, The Medieval Calendar | Comments (4)

Friday, March 25, 2011

Above: Roundel, Annunciation to the Virgin, 1500???1510. South Netherlandish. Colorless glass, vitreous paint, and silver stain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1972 (1972.245.1). See the Collection Database to learn more about this work of art.

March 25 has been a significant date???both religious and secular???throughout Western history. In the Julian calendar, today’s date marked the vernal equinox. In parts of the medieval West, it was used as the first day of the calendar year, although Roman traditions of celebrating the new year in January continued throughout the Middle Ages. (See last year’s post “The January Feast,” January 15, 2010.) Read more »

Tags: Annunciation, The Golden Legend

Posted in The Medieval Calendar | Comments (1)

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

Above: The iron candelabra placed throughout the galleries of The Cloisters are decked with boxwood, ivy, apples, roses, and holly from mid-December until early January. This year’s decorations will be on view through Sunday, January 2. Photograph by Andrew Winslow.

WISHING YOU PEACE, PLENTY, AND EVERY GOOD THING IN THE COMING YEAR.??

???Deirdre Larkin and the staff of The Cloisters Museum & Gardens

Tags: apples, boxwood, holly, ivy, roses

Posted in The Medieval Calendar | Comments (2)

Friday, December 10, 2010

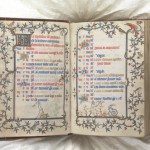

The calendar pages of medieval Books of Hours were embellished with illuminations depicting the traditional labors or activities associated with the month. Above, two folios showing the activities for December, from the Psalter and Hours of Bonne of Luxembourg, Duchess of Normandy. The Cloisters Collection, 1969. (69.86). (See the Collection Database to learn more about this work of art.) In the detail shown in the center, a man prepares to deal the death stroke to a boar; the detail on the right shows a man cutting firewood with an ax. (The cutting and gathering of firewood is a minor labor, sometimes shown as a late autumn or early winter activity.)

Read more »

Tags: arches, boar, book of hours, firewood, garland, wreath

Posted in The Medieval Calendar | Comments (0)

Friday, December 3, 2010

Above, from left to right: Saint Barbara (detail), mid-15th century, French, Gift of Mr. Edward G. Sparrow, 1950 (50.159); Detail of Saint Barbara from The Virgin Mary and Five Standing Saints above Predella Panels, 1440???46, The Cloisters Collection, 1937 (37.52.1); Saint Barbara (detail), ca. 1490, German, The Cloisters Collection, 1955 (55.166).

Although Saint Barbara is not mentioned in early martyrologies, hagiographies place the early Christian virgin and martyr in the third century A.D. According to The Golden Legend, a popular collection of saints’ lives dating to the thirteenth century, she was martyred on the fifth of December, during the reign of Emperor Maximianus and under the orders of Martianus, the prefect of her city of Heliopolis, in??Phoenicia. Veneration of Saint Barbara was common in both the eastern and western churches by the ninth century, and she remains a popular saint to this day, although her feast is widely celebrated on the fourth rather than the fifth of December. Read more »

Tags: Adonis, anise, Anthesteria, Barbarazweig, Barbarea, Barbarea vulgaris, barley, Eleusinian Mysteries, kykeon, Martianus, Maximianus, pomegranate, Provence, raisin, Saint Barbara, The Golden Legend, wheat, winter cress, yellow rocket

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, The Medieval Calendar | Comments (4)

Friday, March 5, 2010

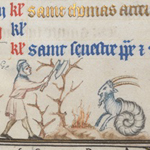

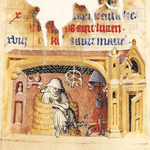

Above, from left to right: Detail of the activity for the month from the March calendar page of The Hours of Jeanne d’??vreux, ca. 1324???28; detail of the activity for March from the Belles Heures of Jean of France, duc de Berry, 1405???1408/1409; detail of the zodiacal symbol Aries from The Hours of Jeanne d’??vreux. See the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History to learn more about manuscript illumination in Northern Europe, or see special exhibitions for information about the exhibition “The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry” (on view at the Main Building March 2 through June 13, 2010).

The month of March marked the return to work in the fields for the medieval peasant, and the pruning, cultivation, and manuring of the vines was the first task of the agricultural year???these essential chores constitute the activity almost always chosen to represent March in medieval calendars. (The spring ploughing of the fields might be shown instead in books of hours made in locales where wine was not produced.) Read more »

Tags: Belles Heures, book of hours, calendar, Jeanne d?????vreux, March

Posted in The Medieval Calendar | Comments (2)

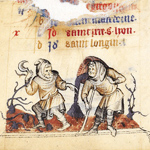

Friday, February 19, 2010

Above, from left to right: Detail of the activity for the month from the February calendar page of ??The Hours of Jeanne d’??vreux, ca. 1324???28; detail of the activity for February from the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry, 1405???1408/1409; detail of the zodiacal symbol Pisces from The Hours of Jeanne d’??vreux. See the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History to learn more about manuscript illumination in Northern Europe, or see special exhibitions for information about the exhibition “The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry” (on view at the Main Building March 2 through June 13, 2010).

In the medieval calendar tradition, the month of February is frequently represented by a solitary male figure seated before a fire; he may or may not be cooking his meal as he warms himself. A table set with a few dishes is sometimes placed by the fire, a variant on the theme of feasting common to both January and February. (See “The January Feast,” January 15, 2010). Read more »

Tags: Belles Heures, book of hours, calendar, February, Jeanne d?????vreux, winter

Posted in The Medieval Calendar | Comments (2)

Thursday, February 11, 2010

Above, from left to right: In The Unicorn is Found, a handsome pair of pheasants has been attracted to the fountain (the larger detail shows two goldfinches and a nightingale perched nearby); two partridges keep company on the bank at the bottom of The Unicorn is Attacked; The Unicorn Defends Itself includes a stately heron, and a woodcock and a mallard flying low to the water are visible in the larger detail.

Saynt Valentyn, that art ful hy on-lofte,

Thus syngen smale foules for thy sake:

Now welcome, somer, with thy sonne softe,

That hast this wintres wedres overshake.

Wel han they cause for to gladen ofte,

Sith ech of hem recovered hath hys make;

Ful blissful mowe they synge when they wake:

Now welcome, somer, with thy sonne softe

That hast this wintres wedres overshake

And driven away the longe nyghtes blake!

???Excerpt (lines 682???692) from The Parlement of Fowles by Geoffrey Chaucer. For a modern prose translation of the complete work, see: www.umm.maine.edu/faculty/necastro/chaucer/pf/.

Read more »

Tags: Chaucer, goldfinch, heron, mallard, partridge, Paston, pheasant, Robert Herrick, Saint Valentine, sparrow, Unicorn tapestries, woodcock

Posted in Plants in Medieval Art, The Medieval Calendar | Comments (3)