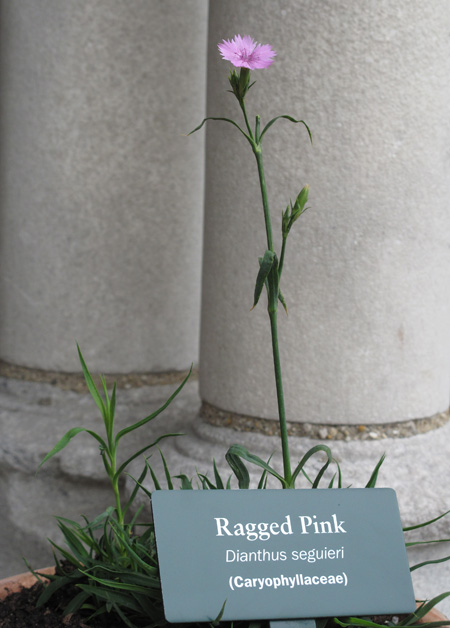

Left: A wallflower in Bonnefont garden shows a cheerful yellow in late November. Wallflowers require a cold period to bloom, and generally flower in spring. Our plants were started indoors from seed and planted out in the garden this summer; the autumn chill spurred them into bloom. Right: Detail of a wallflower blooming above a hunter’s head in The Hunters Enter the Woods (from the Unicorn Tapestries).

The stalks of the Wall floure are full of green branches, the leaves are long, narrowe, smooth, slippery, of a blackish greene colour, and lesser than the leaves of stocke Gillofloures. The floures are small, yellow, very sweete of smell, and made of foure little leaves; which being past, there succeed long slender cods, in which is contained flat reddish seed. The whole plant is shrubby, of a wooddie substance, and can easily endure the colde of winter.

???John Gerard, “Of wall-Floures, or yellow Stocke-Gillo-floures,” Chap. 119, The Herball, or Generall Historie of Plants, 1633

The sweetly perfumed common wallflower (Erysimum cheiri) belongs to the mustard family, or Brassicaceae, along with such pungent vegetables as cabbage and horseradish. It is in no way related to the sweet violet, Viola odorata, or to the spicy-smelling clove pink (Dianthus caryophyllus), but it bore ancient and medieval names associated with both, to the confusion of plant and garden historians. The name “violet” was applied to more than one sweet-smelling species by the ancients; the French girofle and the English “gillyflower” given to the pink derived from the Latin name for clove, but in England a number of fragrant garden flowers in the mustard family, including stock (Matthiola incana),??dame’s rocket (Hesperis matronalis), and wallflower, were all known as “stock gilliflowers.” John Harvey, an authority on medieval plants and gardens, identified the sweet-smelling kheiri mentioned in medieval Islamic sources with this same group of closely related plants. The fourteenth-century Dominican friar and horticulturist Henry Daniel didn’t regard the yellow wallflower, a native of Southern Europe, as a well-known plant in England, although he admired it and thought it easy to grow. While Daniel notes that the plant was called keyrus by the Saracens, it was known to him as Viola major, or “great violet.”

The Greek herbalist Dioscorides had discussed several plant forms under the single name of “Leukion,” or “white violet.” He noted that there were white, yellowish, blue, and purplish varieties of leukion, and that the yellowish variety was best for medicinal use. Medieval herbalists followed Dioscorides in regarding all these forms as varieties of a single plant, but Renaissance botanists and plantsmen like William Turner and John Gerard distinguished between the white or purplish-flowering “stock gilliflowers” and the yellow-flowering “cheiry,” or wallflower, in their reading of Dioscorides.

The history of the common English name “wallflower” is less convoluted: Gerard says that the wallflower grows on brick and stone walls, in the corners of churchyards everywhere, and on rubbish heaps and other stony places, flowering all year long, but especially in winter.

???Deirdre Larkin

Sources:

Anderson, Frank J., ed. “Herbals through 1500,” The Illustrated Bartsch, Vol. 90. New York: Abaris, 1984.

Gerard, John. The Herbal or General History of Plants. The Complete 1633 Edition as Revised and Enlarged by Thomas Johnson. New York: Dover, 1975.

Gunther, Robert T., ed. The Greek Herbal of Dioscorides, translated by John Goodyer 1655. 1934. Reprint: New York: Hafner Publishing, 1968.

Harvey, John H. “Gilliflower and Carnation.” Garden History, Vol. 6, No. 1 (Spring, 1978), pp. 46-5

____Medieval Gardens. Beaverton, Oregon: Timber Press, 1981

Turner, William. The Names of Herbes, A.D. 1548. Edited by James Britten. London: N. Tr??bner & Co., 1881.