Archive for the ‘Gardening at The Cloisters’ Category

Friday, February 25, 2011

A medieval technique of hard pruning, known as pollarding, is used on the four crab apple trees in Cuxa Cloister garden to control the height of the trees and the spread of their canopies. The pruning is done in late winter, while the trees are still dormant.

Above:??Frances Reidy, our arborist, cutting last spring’s growth back to the same “head” as the previous spring’s. This successive hard pruning produces the “knuckles” of tissue characteristic of pollarded trees. This is the third year in which the technique has been applied; the knuckles at the head of the branches will become more pronounced as the pollard matures.

Read more »

Tags: ash, crab apple, Cuxa Garden, pollarding, willow

Posted in Gardening at The Cloisters, Medieval Agriculture | Comments (6)

Friday, February 18, 2011

Above: Both bitter and sweet oranges were introduced into Europe from Asia, but the bitter species preceded the sweet species by??five centuries. The bitter Citrus aurantium var. myrtifolia, a sport, or spontaneous mutation, of the medieval species suitable for pot culture, overwinters on the sunny side of the Cuxa Cloister arcade. The fruit of Citrus aurantium is economically important as a flavoring, although it is too bitter to eat out of hand. The sweet orange, Citrus sinensis, depicted in The Unicorn is Found, would have been introduced only about fifty years before the tapestry was designed.

The bitter orange, Citrus aurantium, spread from its native China to India in ancient times. The orange is mentioned in an early Ayurvedic medical text, Charaka Samhita. According to food historian Alan Davidson, the Sanskrit “naranga” became naranj in Arabic, narantsion in post-classical Greek, and aurantium in Late Latin. Albertus Magnus, the first medieval writer to describe the bitter orange, called the fruit “arangus,” from which the Italian arancia and the French and English “orange” all derive. Read more »

Tags: Ayurvedic, Charaka Samhita, Citrus aurantium, Citrus sinensis, limonaia, myrtifolia, orange, orangerie, stomachic, Tacuinum Sanitatis

Posted in Gardening at The Cloisters, Plants in Medieval Art | Comments (2)

Thursday, February 10, 2011

Robert Campin and Workshop (South Netherlandish, Tournai, ca. 1375???1444). Triptych with the Annunciation, known as the “Merode Altarpiece,” ca. 1427???32. Made in Tournai, South Netherlands. Oil on oak. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1956 (56.70a???c). See Google Art Project for an in-depth look at this work.

A great many things have changed during the twenty years that I’ve been working at The Cloisters, but its special atmosphere remains constant. One of the most unique aspects of the Museum is the way in which the gardens are integrated into the collection. From the Museum’s inception, the curators envisioned the artwork and gardens as a whole, where the plants were not merely aesthetic elements, but also of great educational value. Many of the galleries either open directly onto or provide views into one of the three interior gardens (see floor plan). This arrangement encourages visitors to experience the gardens as part of medieval culture, to make connections between the plants and the objects, and to understand both within the historical context presented in the galleries. Read more »

Tags: Antonites, Bellis perennis, Claviceps purpurea, corn poppy, Cuxa Garden, English daisy, ergotism, fungus, Galen, grain, hermit, ignis sacer, Isenheim, mandrake, Matthias Gr??newald, monasticism, Niclaus of Haguenau, plantain, poppy, sage, Saint Anthony Abbott, Saint Anthony's Fire, Saint Vinage, Tau cross, verbena

Posted in Gardening at The Cloisters, Plants in Medieval Art | Comments (1)

Monday, November 22, 2010

Above from left to right: Margaret Freeman in her office at The Cloisters in 1938; a large and lovely rendering of Lilium candidum prominently placed in the flowery field below the enclosure of the Unicorn in Captivity; tracing of a woodcut image illustrating the entry for the same species of lily, taken by Freeman from the herbal of Apuleius Platonicus, sometimes known as the Pseudo-Apuleius. The Latin subscription states that this lily was known to the Greeks as “Crinion.”

This is not the lily which today is and tomorrow is cast into the oven; it will blossom for ever.

???Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermon 70 on the Song of Songs, III.6

Margaret B. Freeman was associated with The Metropolitan Museum of Art for fifty-two years, first as a lecturer at the old Cloisters in 1928, then as a curator, and eventually as director of The Cloisters in 1955, succeeding James Rorimer. Charged with the development of the gardens, Ms. Freeman was perhaps the single most important contributor to the list of medieval plants drawn from historical sources, which is still in use here. Read more »

Tags: Crinion, James Rorimer, Lilium candidum, lily, Margaret Freeman, Pseudo-Apuleius

Posted in Gardening at The Cloisters | Comments (4)

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

The pretty, fragrant lesser calamint flourishes in all three of the enclosed gardens at The Cloisters. Each small shrub bears a host of delicate little flowers from late summer through frost. Above, from left to right: The lipped flowers of calamint are characteristic of members of the Labiatae, or mint, family; cold weather brings out the purplish cast in the flowers; calamint is beautiful even in winter, when the fine stems are bare.

The larger-flowered calamint, known as Calamintha grandiflora, is frequently grown in modern gardens, but the lesser calamint, Calamintha nepeta, is the calamint of the Middle Ages. Read more »

Tags: calamint, Calamintha grandiflora, Calamintha nepeta, Calamintha officinalis, Cuxa Garden, marjoram, nepitella, Satureja hortensis, Satureja montana, savory, White Cloud

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, Gardening at The Cloisters, Medicinal Plants | Comments (1)

Friday, November 12, 2010

The common name of feverfew is derived from the Latin febrifuge. Botanists now place this member of the aster family in the genus Tanacetum, but feverfew was formerly known both as Chrysanthemum parthenium and Pyrethrum parthenium and may be listed as such in older sources. Above, left and center: Feverfew??growing in Bonnefont garden in November; right: the only feverfew plant depicted in the Unicorn Tapestries appears between the feet of the hunter poised to spear the quarry in The Unicorn Defends Itself.

Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium) is a strongly aromatic herb in the aster family; it is closely related to costmary (Tanacetum balsamita) and to tansy (Tanacetum officinale), both of which also grow in Bonnefont garden. While tansy has been employed as a medicine, a food, and an insect repellent, feverfew is strictly a medicinal herb. The medieval name of this antipyretic??species is derived from the Latin febrifuge and refers to its usefulness in driving off fever. Read more »

Tags: antipyretic, balsamita, Capitulare de Villis, Centaurium erythraea, centaury, Chrysanthemum, costmary, febrifuge, febrifugiam, feverfew, herb, Herbarius Latinus, Hortulus, Pyrethrum, Tanacetum, Tanacetum officinale, tansy, Unicorn tapestries, Walahfrid Strabo

Posted in Gardening at The Cloisters, Medicinal Plants, Plants in Medieval Art | Comments (0)

Friday, November 5, 2010

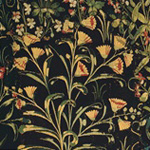

The golden flowers of the calendula, said to bloom in every month of the year, figure in the art, literature, and medicine of the Middle Ages. Called “golds” in medieval English, the flowers were associated with the Virgin and came to be known as “marigolds” by the sixteenth century. Above, from left to right: Detail of a large calendula plant, bearing many blooms, which appears below the golden fence enclosing The Unicorn in Captivity; a calendula blooming in December; the daisy-like flower is often shown in profile in medieval depictions, as in this detail of an urn with three calendula flowers shown in the foreground of a silver-stain roundel depicting the Adoration of the Magi.

‘Golde [Marigold] is bitter in savour

Fayr and zelw [yellow] is his flowur

Ye golde flour is good to sene

It makyth ye syth bryth and clene

Wyscely to lokyn on his flowres

Drawyth owt of ye heed wikked hirores

[humours]. . . .

Loke wyscely on golde erly at morwe [morning]

Yat day fro feures it schall ye borwe:

Ye odour of ye golde is good to smelle.’

???From the herbal of Macer, as quoted in A Modern Herbal

Read more »

Tags: Adoration of the Magi, calendula, Crocus sativus, Konrad von W??rzburg, Macer, marigold, pottage, saffron, Unicorn in Captivity

Posted in Gardening at The Cloisters, Medicinal Plants, Plants in Medieval Art | Comments (0)

Friday, October 29, 2010

The edible weeds that grew among the cultivated vegetables in the medieval kitchen garden were also harvested and used as potherbs. Above, from left to right: purslane, a succulent weed of fertile soils, is a common weed in our own vegetable gardens; lamb’s quarters, also known as “fat hen,” is now a very common weed in the United States; Good King Henry is related to the nutritious lamb’s quarters and was cultivated as a vegetable. Photographs by Corey Eilhardt.

A weed is a plant you don’t want. An herb is a plant with a use. But many of the “weedy” species that are considered garden nuisances today were actually valued in the Middle Ages. Edible weeds growing in the kitchen garden, along with the cultivated vegetables, were used in pottage, a basic medieval dish. (For more on pottage, see last week’s post, “Colewort and Kale.”) Read more »

Tags: cabbage, Chenopodium album, Chenopodium bonus-henricus, dandelion, Good King Henry, herb, kale, lamb's quarters, leek, Portulaca oleracea, pottage, purslane, ribwort plantain, weed

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, Gardening at The Cloisters, Medicinal Plants | Comments (4)

Friday, October 22, 2010

The Brassicaceae, or mustard family, contains many vegetables with a long history in the European diet. Cabbage, kale, broccoli, and cauliflower are all forms of a single polymorphic species, Brassica oleracea. Above from right to left: Collard is the closest available approximation to the colewort, the primitive cultivated cabbage of the Middle Ages. The tight, heading cabbages we know today were developed from the colewort. Sea kale (Crambe maritima), which was gathered from the wild, belongs to a separate genus within the Brassica family.?? Photographs by Corey Eilhardt.

Cabbages and kales have been eaten, improved, and eaten some more for centuries. The medieval cabbage, or colewort, (see the first image for the etymology of “colewort”) was one of the mainstays of the medieval diet, at least for those ordinary mortals outside courtly circles, whose more refined cuisine has been preserved in cookbooks???such as the famous Forme of Cury???of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The greens were cooked and eaten alone, or were included in pottage???sometimes spelled “potage”???a kind of thick soup or porridge made from vegetables boiled with grain. Read more »

Tags: Brassica oleracea, Brassicaceae, broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, colewort, Crambe maritima, gout, kale, Landsberg, mustard, palsy, ulcer

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, Gardening at The Cloisters | Comments (1)

Friday, October 15, 2010

Many of the healing herbs, flowers, and foodstuffs mentioned by the twelfth-century Benedictine abbess Hildegard of Bingen in her great work Physica are grown in Bonnefont garden at The Cloisters. Above, from left to right: Field peas (Pisum sativum arvense,??variety ‘Blue Pod Capucijners’); Madonna lily (Lilium candidum); milk thistle (Silybum marianum).?? Photographs from the Gardens archives.

It is the first book in which a woman discusses plants and trees in relation to their physical properties. It is the earliest book on natural history to be done in Germany and is, in essence, the foundation of botanical study there. It influenced the 16th-century works of Brunfels, Fuchs, and Bock, the so-called ???German fathers of botany,??? but the fact is that German botany is more indebted to a ???mother.???

???Frank Anderson on the Physica, from An Illustrated History of the Herbals

Certain plants grow from air. These plants are gentle on the digestion and possess a happy nature, producing happiness in anyone who eats them. They are like a person???s hair in that they are always light and airy. Certain other herbs are windy, since they grow from the wind. These herbs are dry, and heavy on one???s digestion. They are of a sad nature, making the person who eats them sad. They are comparable to human perspiration. Moreover, there are herbs which are fatal as human food . . . they are comparable to human excrement.

???From Book I of the Physica, translated by Priscilla Throop

Hildegard of Bingen, Benedictine abbess, visionary, poet, dramatist, composer, and the most learned woman of the twelfth century, wrote the Physica, or Natural Science, about the year 1150. Read more »

Tags: Bonnefont Garden, field peas, Hildegard von Bingen, lily, medicinal plant, milk thistle, Silybum marianum

Posted in Botany for Gardeners, Gardening at The Cloisters, Medicinal Plants, Plants in Medieval Art | Comments (4)