Archive for the ‘Gardening at The Cloisters’ Category

Thursday, October 24, 2013

While rosemary was a familiar herb of the Mediterranean littoral in antiquity, the date of its introduction into Northern Europe is uncertain, and it was not grown in England until the fourteenth century. The thorn apple, Datura metel, did not reach Europe from India until the fifteenth century, although it is mentioned in Islamic sources at an earlier date.

Much as architectural elements from different periods and locales in medieval Europe were transported to New York and integrated into a single modern building, the herbs, fruits, and flowers growing in the gardens were transplanted, traveling across time and space to their home at The Cloisters.

Read more »

Tags: Datura, Datura metel, rosemary, thorn apple

Posted in Gardening at The Cloisters, The Medieval Garden | Comments (3)

Friday, October 11, 2013

Carol Schuler, a garden lecturer at The Cloisters, discussed autumn in the medieval agricultural year. One component of her presentation in Bonnefont herb garden was about cultivating hops, an aggressive climbing bine seen growing in this photograph, which was used in medieval beer brewing. Photograph by Nancy Wu

We were graced with beautiful weather last Saturday, October 5, as we hosted our first Fall Garden Day, devoted to discussions on medieval gardening and the medieval harvest. Visitors enjoyed wonderful talks and activities led by staff and lecturers, whose discussions ranged from seed collecting to medieval beekeeping. This special Fall Garden Day was organized to celebrate The Cloisters’ seventy-fifth anniversary, and was a fine complement to our annual Spring Garden Day, which explored medieval fruit. Come visit the gardens while this pleasant fall weather continues!

Visitors who participated in Fall Garden Day greatly enjoyed the presentation by Roger Repohl, a very enthusiastic and knowledgeable beekeeper. Roger discussed honeybees and beekeeping in the Middle Ages. Photograph by Nancy Wu

Tags: bee, beekeeping, bine, Garden Day, harvest, hops

Posted in Gardening at The Cloisters | Comments (2)

Friday, September 27, 2013

Beautiful Blue Pod Capucijner (Pisum sativum arvense, var. ‘Blue Pod Capucjiner’) seedpods and seeds. All photographs by the author

How many of you gardeners out there take the time to save your garden seed? The allure of planting seeds in the spring is easy to understand, but do you linger over drying seedpods later in the season, waiting to harvest next year’s generation? Seed saving may seem like an onerous counterpart to seed sowing, but the task is endlessly rewarding. It’s not just about securing a free source of new plants for the following year or two; there are other benefits to reap, so to speak. By selecting seed from among the garden’s most healthy specimens you promote added vigor in subsequent generations of plants. You get to witness the often overlooked beauty of a plant engaged in seed production. And, really, is there anything more satisfying than sowing the seed you collected from your own garden? For the seed-saving gardener, it doesn???t get much better than that.

Read more »

Tags: Blue Pod Capucijner, castor bean, corn poppy, Datura, Datura metel, Glaucium flavum, henbane, horned poppy, Mandragora officinarum, mandrake, Ricinus, sea poppy, seed, seedhead, seedpod, seeds, stavesacre

Posted in Botany for Gardeners, Gardening at The Cloisters | Comments (3)

Friday, September 6, 2013

The Unicorn in Captivity (from the Unicorn Tapestries) (detail), 1495???1505. South Netherlandish. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1937 (37.80.6). See Collections to learn more about this work of art. The red-flowered plant that appears to the left of the blue iris, just outside the Unicorn’s enclosure, is a carnation, a doubled garden form of the clove pink. Unlike the iris, which was already of ancient cultivation, these garden pinks were developed in the later Middle Ages.

LUXURIOUS man, to bring his vice in use,

Did after him the world seduce,

And from the fields the flowers and plants allure,

Where Nature was most plain and pure.

He first inclosed within the gardens square

A dead and standing pool of air,

And a more luscious earth for them did knead,

Which stupefied them while it fed.

The pink grew then as double as his mind;

The nutriment did change the kind.

With strange perfumes he did the roses taint;

And flowers themselves were taught to paint.

???Andrew Marvell (1621???1678), “The Mower Against Gardens,” Lines 1???12

This complaint, in which a mower laments that the sweet fields have been forsaken for the artificialities of the English Renaissance garden, was penned by Andrew Marvell, the seventeenth-century Metaphysical poet, who wrote as famously and well of gardens and their plants as he did of fields and wildflowers. In “The Mower Against Gardens,” Marvell chooses the doubled pink, or carnation, as the floral emblem of man???s fall from nature and agriculture into horticulture and duplicity. (A reading of the entire poem is available on YouTube.)

Read more »

Tags: carnation, clove pink, Dianthus caryophyllus, pink

Posted in Gardening at The Cloisters, Plants in Medieval Art | Comments (1)

Wednesday, August 28, 2013

Leila Osmani, a security guard who has worked at The Cloisters for six years, gazes out into Cuxa cloister garth garden in the morning before the Museum opens. In the Middle Ages, this garden would have provided the monks with refreshment and nourishment.

In the Middle Ages the color green symbolized rebirth, life, everlasting life, nature, and spring. I think it is fair to say that these attributions hold true to this day.

The twelfth-century mystic and theologian Hugh of St. Victor believed that green was the “most beautiful of all the colours” and a “symbol of Spring and an image of rebirth.” His theory was supported by William of Auvergne, who said the color “lies halfway between white, which dilates the eye, and black, which makes it contract,” creating a calm sensation, especially when viewed in great expanse.

Read more »

Tags: garth, green, lawn

Posted in Gardening at The Cloisters, The Medieval Garden | Comments (8)

Friday, August 9, 2013

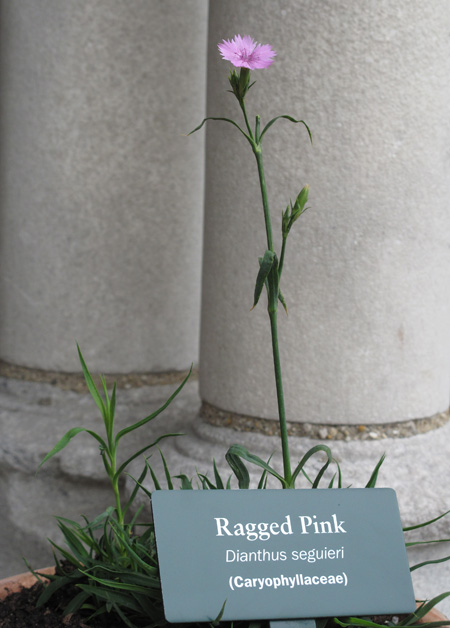

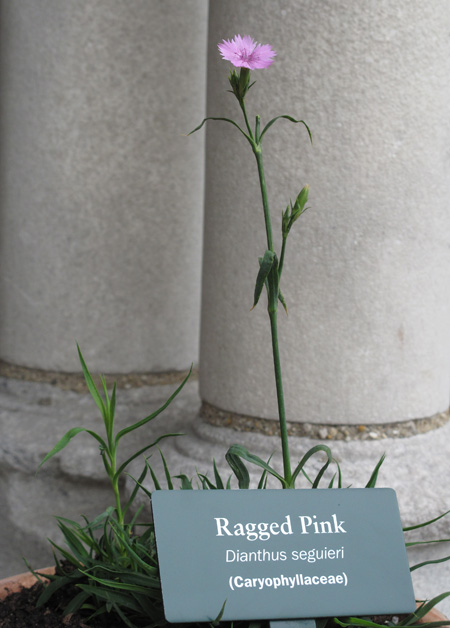

The ragged pink shown above, also known as Seguieri’s pink or broad-leaved pink, is native to southwestern Europe. This prettily fringed, or “pinked,” flower is one of three species of dianthus depicted in the Unicorn Tapestries. But is this dianthus, grown from seed just this year, the wild pink depicted in the detail from The Hunters Enter the Woods below?

The little pink growing in a pot on the parapet in Bonnefont garden was started from seed by gardener Esme Webb, who is responsible for propagation at The Cloisters. As has been the practice here for many years, we compare what we believe to be the medieval species procured with representations of that plant in the art collection. Although the seed we obtained from a European seed house was identified as Dianthus seguieri, the single flower borne on this young plant either lacks the white blotching characteristic of this species altogether, or has blotching so minimal as to be imperceptible. Read more »

Tags: dianthus, Dianthus seguieri, pink, Unicorn tapestries

Posted in Gardening at The Cloisters, Plants in Medieval Art | Comments (2)

Thursday, June 13, 2013

It is June, it is June,

the pomegranates are in flower,

the peasants are bending cutting the bearded wheat.

The pomegranates are in flower

beside the high road, past the deathly dust,

and even the sea is silent in the sun.

Short gasps of flame in the green of night, way off

the pomegranates are in flower,

small red flowers in the night of leaves.

And noon is suddenly dark, is lustrous, is silent and dark

men are unseen, beneath the shading hats;

only, from out the foliage of the secret loins

red flamelets here and there reveal

a man, a woman there.

???Andraitx???Pomegranate Flowers, by D.H. Lawrence

From left to right: The vivid scarlet blossoms of a potted dwarf pomegranate tree in full flower glow against the gray stone of the blind arcade in Bonnefont garden; detail of pomegranate flowers. Both dwarf and standard forms of pomegranate are grown here. Although cultivated for hundreds of years, the dwarf form is not medieval, but it lends itself to pot culture, and can be more easily managed than the full-sized tree. Photographs by Carly Still

Although these photographs were taken just a few days ago on a gray day in Bonnefont garden, this post is coming from sunny California, where I am participating in a panel discussion on museums and gardens at the Getty Center in conjunction with an exhibition curated by Bryan Keene. Read more »

Tags: bay, fig, laurel, olive, pomegranate

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, Gardening at The Cloisters | Comments (6)

Friday, June 7, 2013

A beautiful plant related to the ornamental delphiniums and larkspurs of our gardens, stavesacre is a poisonous member of the buttercup family. Its seeds were used topically to kill scabies and lice in antiquity and in the Middle Ages. Since this Mediterranean native isn’t winter hardy in our climate, seeds must be started indoors or in a cold frame; the young plants are set out once the danger of frost is past.

Read more »

Tags: buttercup, delphinium, Dioscorides, Ranunculaceae, stavesacre

Posted in Gardening at The Cloisters, Medicinal Plants | Comments (7)

Thursday, May 30, 2013

Left: Blossom on espaliered pear tree. Photograph by Corey Eilhardt; Right: Fruit on the espaliered pear in Bonnefont garden. Photograph by Barbara Bell

Join us on Saturday, June 1, for a special Garden Day, celebrating the seventy-fifth anniversary of The Cloisters museum and gardens. We’ll be discussing our fruit trees in a daylong program of events, including talks on the significance of orchards and orchard fruit in medieval life and art, medieval fruits you can grow today, training and pruning espaliered trees like our famous pears, and the care of our beloved quince and other orchard fruits.

For related information, see previously published posts about our pear, medlar, and cornelian cherry trees.

—Deirdre Larkin

Tags: cherry, fruit, medlar, orchard, pear, quince

Posted in Gardening at The Cloisters | Comments (2)

Friday, May 24, 2013

Left: Angelica silhouetted against the blind arcade in Bonnefont cloister. Modern gardeners admire the bold, architectural qualities of angelica as an ornamental plant, but it has a long history as a useful herb. Right: The flower structure is typical of the carrot family to which it belongs. Photographs by Carly Still

Unknown to the Greeks and Romans, the beautifully named Angelica archangelica is a native of northern Europe. It can be difficult to determine whether it is this “garden angelica” or its close relative, A. sylvestris, that is under discussion in early sources, although Renaissance plantsmen like John Gerard distinguished between the two (see images of A. sylvestris in the wild).

Read more »

Tags: angelica, Angelica archangelica, Angelica sylvestris, asafoetida, carrot, parsley

Posted in Food and Beverage Plants, Gardening at The Cloisters, Medicinal Plants | Comments (0)