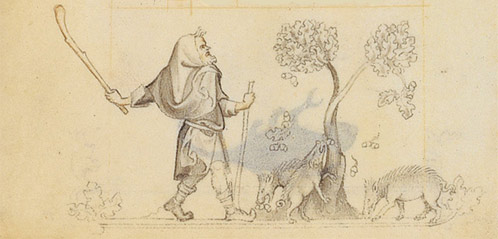

Above, from left to right: Calendar page for November from the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry, 1405???1408/1409. Pol, Jean, and Herman de Limbourg (Franco-Netherlandish, active in France, by 1399???1416). French; Made in Paris. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1); detail of the activity for the month; detail of the zodiacal symbol Sagittarius. See the Collection Database to learn more about this work of art.

The term “mast” was applied to any autumnal fodder on which pigs might forage, including beechnuts, haws (the fruit of the hawthorn), and acorns, as well as fungi and roots. Acorns were the principal fodder in fattening up swine to be slaughtered and salted for winter food. While green acorns contain toxins that are poisonous to cattle and to people, they are not harmful to pigs. (Pigs were not reared in winter. Once the boar had sired a litter, he was sacrificed. Bacon and hams were cured after the November slaughter. Bacon grease replaced butter as the principal fat in the winter diet.)

“November???s Husbandrie” from Thomas Tusser???s Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandrie, 1580.

A swineherd carrying a pole or stick to knock down acorns for his pigs frequently appears in the calendar tradition as the activity proper to November, as in the detail from the Belles Heures shown above. A very similar scene is depicted on the November page of the Tr??s Riches Heures.

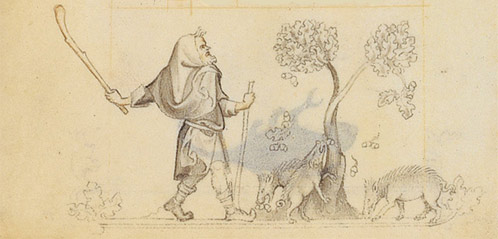

The same subject is drawn in ink on the lower left margin of the November calendar page of the Hours of Jeanne d’??vreux, currently on display in the Treasury at The Cloisters. Jeanne, queen of France, retained the right to the income from the harvest of acorns in the forest of Nogent for her lifetime.

Jean Pucelle (French, active in Paris, ca. 1320???1334). Detail from the November calendar page from The Hours of Jeanne d’??vreux, ca. 1324???1328. Grisaille and tempera on vellum; 3 1/2 x 2 5/8 in. (8.9 x 6.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.2). See the Collection Database to learn more about this work of art.

In medieval forest law, certain rights and privileges were afforded the tenants on the lord???s woodlands; the term ???pannage??? was used to designate both the practice of bringing pigs to the wood to forage for mast, and the right or privilege to do so. The term could also be applied to payment made to the owner of the woodland in exchange for this privilege, or to the owner???s right to collect payment, or to the income accruing from the privilege.

In England, where the tradition of foraging swine in oak forests was an important part of the agricultural cycle, the Saxon rights of pannage were much reduced by the Norman enclosure of game preserves, and the Saxon diet was greatly reduced when their pigs were deprived of acorns.

Acorns contain fat, carbohydrates and protein. The acorns of the common oak of Britain and northwestern Europe (Quercus robur) have a high tannin content and are too bitter to be palatable, but have been eaten in times of famine. They were ground into a meal that afforded a coarse bread. Alan Davidson notes that both acorns and bread or cakes made from them have remarkable keeping powers.

The Mediterranean holm oak (Quercus ilex var. rotundifolia) bear acorns that are much sweeter, and these are still enjoyed in Spain and Portugal, much as chestnuts are. It is probably the acorns of this species, when roasted and eaten with sugar,??that are recommended as a health-giving food in the Tacuinum Sanitatis, a late medieval health handbook based on an eleventh-century Arabic source.

???Deirdre Larkin

Sources:

Arano, Luisa Cogliati. The Medieval Health Handbook: Tacuinum Sanitatis. New York: George Braziller, 1976.

Davidson, Alan. The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Hartley, Dorothy. Lost Country Life. New York: Pantheon Books, 1979.

Husband, Timothy B. The Art of Illumination. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008.

P??rez-Higuera, Teresa. Medieval Calendars. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1997.